Hello, friends!

I’ve been accused of being a bit random in my choice of topics and transitions in this blog.

This weekend, I put blood, sweat, and tears, and a decent piece of my thumb, into a delicious fried rice lunch. I’m doing all right and didn’t have to go to the hospital. How was your weekend?

A lot of people are up in arms about generative AI right now—particularly with regards to its ability to generate images. (A lot of interesting developments are coming out nearly every week around this topic—like federal judges ruling that AI artwork cannot be copywritten. I wouldn’t be surprised if all AI work will ultimately be judged the same.) Since I tend to diverge from popular sentiment in a lot of areas, I decided to put my current thoughts here.

Before we start, what are your general feelings on AI?

Neutral.

What does neutral mean?

It means I acknowledge that the world constantly changes, some things individually for the better or worse, but I see a general upward trend, and I don’t think AI breaks that pattern. I think it’s ridiculous to get as angry about AI as some people are. While I don’t think there’s anything wrong with expressing concerns or pointing out potential issues with AI, I think the people who are allowing themselves to be controlled by existential fear or paralyzing anxiety are being foolish. No good ideas or actions are born of anger or fear.

Seriously?

Yeah. If my feathers don’t need to be ruffled, why waste the energy?

All right, then. Let’s shift from general AI to image-generating AI specifically. Are you concerned that image-generating AI will disrupt the art industry?

No.

You don’t believe it will?

I didn’t say that. (Why do all interviewers insist on putting words in your mouth?) I believe that AI-generated images have already created quite a disruption, and I think they are just getting started. But I don’t think that’s a bad thing; at worst, it’s the price of technological advancement, which is net-positive.

Let me expand on that. All industries, everywhere, have been disrupted at one point or another, with natural disruptions ultimately being a good thing. People who made a living sewing clothes probably weren’t happy about the invention of sewing machines—the ones that don’t require human involvement, anyway—but I would rather live in a world with factory-produced clothing, and the convenience and cost saving that provides. People who made a living fixing typewriters probably didn’t like computers and word processors, but thank God they didn’t stop progress! Similar comparisons can be made anywhere else.

Yes, the speed and cost-efficiency of AI-generated images will mean some artists will lose their jobs. And for the artists who lose their jobs, that really does suck, and it will be a hardship for them. Change is hard, and some will need help—maybe a lot of it—transitioning to a different type of work. But that doesn’t necessarily mean they won’t still produce art for a living—consider the above examples I provided. People still sell handmade clothes at high prices, some making a living off of that, with the justification behind the higher prices being that the clothes are artisanal. Artists of images may find themselves in such a position.

In the meantime, beautiful images of good quality will become more available for everyone. Speaking as a starving artist with a very low budget for cover art, that’s a huge boon. There are thousands of other people like me who don’t need, or can’t afford, what traditional artists provide, and giving us the resources we need to thrive is a good thing.

Would you rather live in a world where you were forced to travel by horse and buggy because cars would have “disrupted the industry,” or would you rather have a modern car or truck?

But this is art. Those are tools, basic necessities, and the like.

So? On a survival level, art is far less necessary than those things—it’s a commodity. We don’t need it, strictly speaking.

I mean, yes, we want art to elevate, enrich, and inspire, and if people get that from AI-generated art then they shouldn’t be stopped from that. And if they don’t, then they won’t buy AI-generated art. In short, let the invisible hand of the market do its job.

Are you concerned about AI-generated images stealing artwork?

To my knowledge, your question encompasses a ton of not-directly-related scenarios that can’t be answered with one response. I’ll specify two examples.

If what you are referring to is AI image generators using the artwork of existing artists to learn how to produce art, based on my understanding of the process I don’t have an issue with it. After all, any human artist can find most of the artwork of any given artist for free online; if that human artist wanted to, she could study the artwork in detail, study the life and style of the author, and intentionally train herself to create art that emulates—perhaps to an uncomfortable degree—the artist she studied. No one would say she was doing anything wrong. While AI learning from art and using what it learned to generate images is not an identical scenario, my understanding of the technology and algorithms behind it (which, I fully admit, is very limited) is that the two are parallel enough that I think the situations should be treated more-or-less the same. (The exception would be art that was accessed illegally as part of training AI. AI learning from art with a copyright expressly forbidding such a thing… I’m not sure on that one. An artist can’t expressly forbid humans from learning from her art work if it is otherwise legally accessible for viewing.)

If what you are referring to is AI image generators producing work nearly identical (or completely identical) to existing artwork, that might be theft. I’m not aware of anything being brought to court and confirmed theft; I would side with the artist suing for copyright infringement in that particular instance, but I think the solution would be to modify the image-generating AI with safeguards to prevent it from producing anything that looks too similar to any of its sample images.

Are you afraid of AI coming for other fields? For example, AI-produced books are already being sold on Amazon.

And have you seen how utterly terrible the writing in those books is?

All right, all right, AI can—kind of—write nonfiction decently well. There is the issue of completely making up facts and sources sometimes, and then if you question the AI it attempts to gaslight you into believing everything it does is 100% accurate, but the quality of the writing itself is passable; I’ve been told it’s about the level of a competent college freshman. That’s not great, but it is better than the average.

However, in the realm of fiction, AI can’t do anything right. AI doesn’t understand emotion at all and, since emotion isn’t logical and AI runs entirely on logic models, I’m not convinced it ever will. (Strictly speaking, that doesn’t mean it can’t eventually convincingly model or simulate emotion eventually, but it’s got a steep uphill battle.) AI also isn’t very creative—it can’t really produce anything new or interesting, something completely made up that hasn’t been seen before (or an imaginative version of existing things that feels fresh) because it’s designed to exclusively take data it already has, make pattern predictions based on that data, and spit something plausible-but-random out in a reconfigured way. So, for the time being anyway, I have no concerns about AI rendering my desired career automated.

And if it does?

Then I will experience the same things image artists are experiencing now, and I’m at peace with that. Admittedly, it’s way less of a threat to me than more successful authors—if AI takes away the $15-or-so that I’ve made this year, that’s one less burger at Five Guys for me. Oh no.

But let me add another thing—maybe I’m past the point where bringing this up adds anything to the conversation, but a friend of mine asked me if I was concerned that AI was flooding the market with cheaply written, crappy books (or would). I showed him Kissing the Coronavirus: Kissing the Coronavirus Chronicles, a romance-sex-novel that was probably written in one evening, features the protagonist meeting (and having sex with) an anthropomorphized version of COVID-19, and features… writing of a certain quality. Here’s some quotes:

His tongue, so soft and hot, like a chunk of microwaved fish, sloshing around inside her mouth.

Kissing the Coronavirus

Even the sound of the virus made her ovaries clash together like cymbals.

Kissing the Coronavirus

(Specifically in reference to that last quote, I would like to note that the author, MJ Edwards, is a woman, not a man who has no idea whatsoever how ovaries work.)

(Also, let me emphatically note that I have not read this book.)

Humans do not need AI to mass-produce super crappy writing to flood the marketplace and, regrettably, get rewarded with unreasonable amounts of success. That’s something writers with some integrity will have reckon with whether AI is in the picture or not.

That’s disgusting.

Isn’t it, though? But also a little fascinating. Over a thousand reviews, and at least successful enough that the author wrote a bunch of sequels. It does not make me reconsider the types of books I want to write, but it does help me understand why people write such shameless crap in the first place.

Virus-related smut aside, are you afraid of the social backlash? People are getting cancelled for not walking in lockstep with the loudest narrative. Heil cancel culture!

Well, that was a tasteless reference there at the end, Mr. Interviewer Sir.

In a practical sense, no. My most dedicated audience is my grandma and my best friend, and they won’t—and can’t—cancel me. I think. (Grandmas love to surprise.) As far as I can tell everyone else reading this blog comes, reads one or two posts, and goes. Hopefully I can fix that with future endeavors, but more on that later…

On a moral level, still no. Even if I did have the kind of audience where “cancelling” was a real risk, I don’t believe in giving in to social fascism/terrorism. State the truth—not your truth, because that doesn’t exist—but what you believe to be objective truth, then have genuine and rigorous conversations with people, be polite (or at least civil) with those that disagree with you, and the best solution will win out in the end. People who are so up-in-arms about AI that they wage war against those who aren’t part of the social police are fools. That’s not to say that there’s anything wrong with disliking, or even hating, AI, and there’s nothing wrong with being vocal about it or trying to persuade people to agree with you—that’s the purpose of speech. But trying to bully or abuse people who disagree with you is flat-out wrong in any context.

Bloggyness Review: Echopraxia

Echopraxia, by Peter Watts, is a hard science fiction novel and “sidequel” to Blindsight. It follows events going on or “near” earth happening more-or-less concurrently with Blindsight.

Where Blindsight ruminated on the nature of intelligence and consciousness (or self-awareness), Echopraxia attempts to have meaningful discourse on faith—and ultimately fails, in my eyes. It is still an interesting read—though nowhere near as strong as Blindsight—but doesn’t stick the landing.

To give Peter Watts and Echopraxia some credit, I vibed with this book at the beginning. A man of faith myself, it was very refreshing to read a book that didn’t treat faith as either evil or the stuff of complete and utter morons. And, at the beginning, I was astonished by how fair-handed Peter Watts was. I felt like he represented faith and belief very well, initially—even for those who aren’t religious, faith (or a belief or hope in something that can’t be empirically proven until it occurs) is still an important principle. Two of the lead characters represented opposite sides of the debate, one decrying the “evils” done in the name of religion and the other pointing out the scientific saint known as Darwin was invoked in entirely science-based efforts of evil and eradication, such as eugenics. This led to one of my favorite quotes from the book:

Let’s just agree that neither side has a monopoly on assholes. The point is, once you recognize that every human model of reality is fundamentally unreal, then it all just comes down to which one works best.

Echopraxis

Both characters also point out the incredible good that science and faith have wrought, and both got so very disappointingly close to realizing how much more good can be multiplied when these two modes of thought are married.

Unfortunately, Echopraxia fails to stick the landing. It’s revealed later in the book that the Bicamerals—the religious order representing the “faith” side of the argument—are just scientists. They don’t actually have faith, religion, or belief; they are just a hive mind that outsiders define as a religious group because they don’t understand it. True, some of the people they work with are bought into the faith and mystique surrounding the Bicamerals, but that doesn’t mean there is anything faith-related of substance here; the Bicamerals ultimately just represent science-but-done-by-transhumans.

This is indicative of a deeper issue held by the characters that might stem from the author himself: the faith-based characters don’t actually believe in anything.

Imagine writing a scientist character that doesn’t believe in, or use, science; a historian that doesn’t believe history exists, or that exclusively makes it up on the spot; such characters would be hollow if played straight, without any real meaning behind who they are or what they represent. Or they would eventually be revealed to be a wolf in sheep’s clothing; either way, they would fail to represent what they were promised to be. This is, in essence, what happened with the Bicamerals, and I don’t think the “subversion of expectations” was justified when the conversation before the subversion was deep and nuanced, but pointless after; it turned into a weaker version of the conversation on consciousness and intelligence that was already nailed in Blindsight.

And the failure isn’t limited to individual characters, but to the conclusive arguments of the book itself. Daniel Bruks, the lead, begins as an anti-faith scientist, but by the end of the book he has been beaten and broken until he is… a man of faith? A prophet? It’s not clear—and I don’t think the book is being cynical or self-destructing from being a story to just parodying faith and religion—but what is clear is that Bruks doesn’t really have faith, he just has changed so that his subconcious has more power than his conscious. And that’s presented as faith. No elements of God, spirits, or anything beyond or outside the mortal meatsuit; just a ridiculous amount of pattern-matching and pattern-predicting power in the human subconscious. A bummer.

(The point is not to say that Peter Watts needs to reorganize these elements to include them in his fictional universe; if he wants to create a sci-fi world without God, he’s free to do so. But that doesn’t mean his religious/faith-driven characters are three-dimensional, believable, or compelling without having them genuinely believe in something. Even if Peter Watts doesn’t believe, his characters need to in order to be whole.)

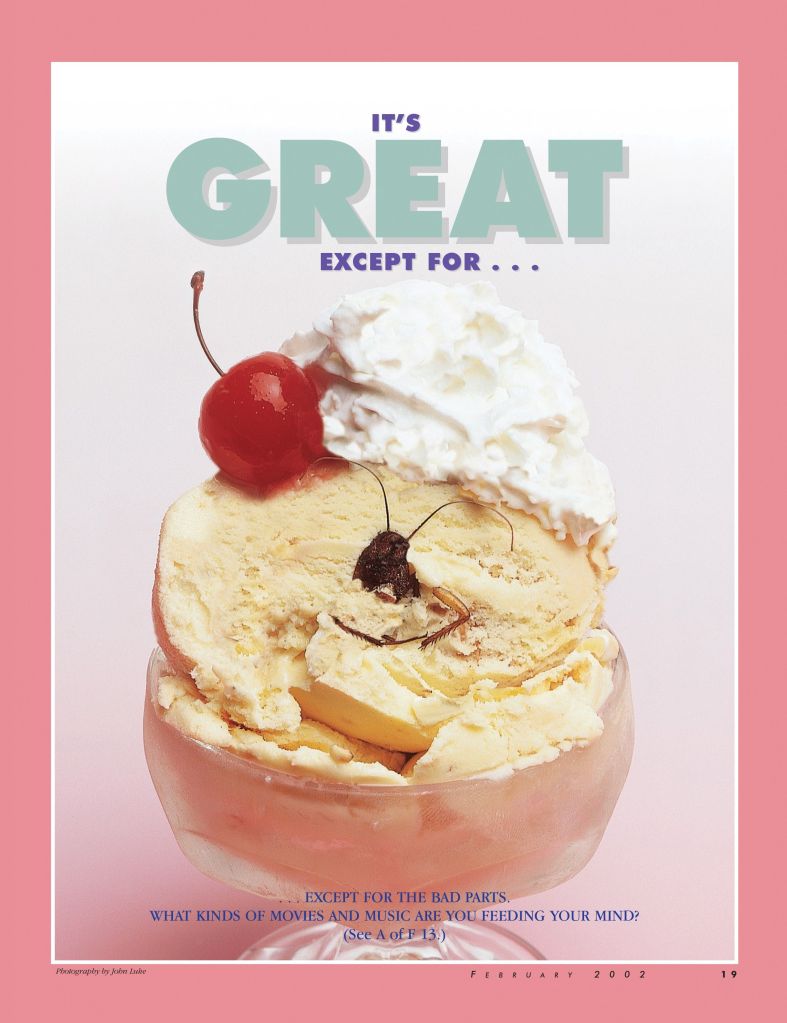

There’s also another issue I have to point out: you got to eat around the roach in this book. Let me explain.

If you were raised a Latter-Day Saint, you’ve probably seen the following poster:

Note that I’m not here to preach to you or tell you what you should find good or bad in your media consumption; that’s not the point of why I’m sharing this poster. I’m sharing this poster because it is a powerful metaphorical image representing how something can be otherwise amazing, but have one bad thing in it that ruins the whole—or could ruin the whole, depending on how particular you are. What counts as a roach differs from person to person—some people don’t mind explicit nudity or sex in their media, but I don’t like it. Some people don’t like any swearing in their media, others don’t mind it at all—I fall somewhere in the middle. My roaches are different from your roaches. As you read more of my stuff, you’ll recognize what my roaches are and better understand what is really being said when I review something and tell you that you may need to eat around the roaches.

Echopraxia can be good, but you need to eat around the roaches—for me, this book has way too much swearing and way too much reliance on crude imagery and metaphor. It turned me off at many points. Obviously I liked the rest of the ice cream enough to finish anyway, but I had to eat around the roach. That’s my content warning for this book.

(Maybe in a future blog post I’ll have a different conversation about whether there is any value in eating around roaches: some people think consuming media that includes things below your standards is hypocritical—particularly if, like me, you then go and talk about what’s good in it, perhaps persuading someone else to give it a try—while others see it as a necessary evil of our modern day. There are far many other opinions besides. Could be worth some thinking.)

Writing Updates

I am 1700 words into The Betrayed Technomancer! Woohoo!

That’s right, it means my short stories are shelved again for the time being, but I couldn’t care less. The Betrayed Technomancer is a much bigger, more impactful project anyway. Expect word count updates each week.

1700 words gets me much of the way through the prologue—this one follows Zed, and provides a lot more insight into who he was and how he became the monster he is. If you enjoyed the conflicted, intelligent rozie in The Failed Technomancer, you’re going to love him in The Betrayed Technomancer.

In addition, soon I’m going to start posting chapters from The Failed Technomancer to this blog. A chapter a week, roughly, and they will be available for free for the foreseeable future. If you haven’t had a chance to read it yet… you’re in luck!

No further updates on other projects—I do plan on writing other things in spare moments, but with how busy my job is and with how much writing I want to do each day on my primary novel I don’t get lots of “other writing time.”

Send-Off

What are some weird story ideas you had, and what you are going to do with them? I had two this week:

- A fantasy world where the gods gave humans a dangerous tool to destroy demons: a horrible, highly infectious plague that annihilates demons rapidly but kills humans very slowly. A priesthood was built around the containment and careful use of the disease: the only way to keep humans safe, but the weapon ready for action, is to always have one person infected and sequestered, but then a new person sent in to get infected when the former nears death. But as the centuries past, people forget the original gift and begin to wonder if the legends are true or just justification for heinous actions… I like the idea of making this a short story, eventually.

- You know the dragon rider archetype? Well, Sanderson proved that can be a lot of fun when twisted, with Skyward as his example. What if the story were changed so that a human took the role of the dragon, and a very small but largely immobile fantasy creature as the rider? Perhaps if the creature imparted some powerful abilities to its ridden human, I could see such a partnership being very enticing.

And that’s it. Have a great week!

Leave a comment