Hello, friends!

I hope that you and yours are doing well.

Me?… Well, let’s just say that potty training a two-year-old is… an experience. Good news is, she wears underwear most of the time and doesn’t usually have accidents. She definitely struggles when we travel, though—and we learned today that church is not the right place to keep her out of a diaper. Not yet, anyway.

Yes, two-year-olds can be potty trained. For home use, anyway. I did not believe it, my wife pushed ahead anyway, and I am extremely happy to be eating crow on this issue.

Discussions—Identity and Boundaries

Take a moment and let yourself drift off into imagination. When I say the word “elf,” what do you imagine?

Odds are (because of the trilogy’s extremely defining influence on what counts as an elf), you thought of something very close to Lord of the Rings‘ vision of elves. Slim, tall, with angular features and pale skin, a regal sort of beauty. Generally wearing beautiful clothing, particularly robes, or maybe armor that is unrealistically beautiful and ornamented on any other creature, but looks just right on the elf. You might imagine a crown made of thin metal or wire, or even made of simple branches and twigs woven together (and looking noble nonetheless).

This is a very defining idea of what an elf is, and it is deeply part of what gives Lord of the Rings its identity—what makes it unique, what gives it a specific flavor that other fantasy either doesn’t have or is (more often than not when attempted) a cheap imitation of.

This identity goes far deeper than appearances. Elves in Lord of the Rings have grace. They are extremely intelligent, or at least knowledgeable. They are very long-lived, and all but the youngest among them have a deep and detailed knowledge of their history. They are generally a good people, though sometimes they fall into vices (like any other flawed creature may)—and there are rare but notable outright villains.

Is this what an elf has to be?

To make another comparison, look at the hobbits—short, round of feature, generally pleasant (if perhaps narrow in vision). Very often good-of-heart, even if some fall prey to quibbling with neighbors or continuing family rivalries. One might call hobbits a simple, happy folk, even though many have proven that there is far greater courage, and ability to endure hardship, in the hearts of the little folk than most are aware of, including themselves.

Is this what a hobbit has to be?

Yes.

Well, these are what elves and hobbits have to be if you want to make a Lord of the Rings elf or hobbit. There’s nothing wrong with another series making such creatures completely different—but I think there is something wrong with making significant changes to elves and hobbits in a Lord of the Rings context.

Why, though?

Because then it ceases to be Lord of the Rings.

Rings of Power runs into this issue, by my estimation. There’s something just… off about the elves in that series, beyond writing issues with dialogue, character competence, and plotting. They generally look right, but they don’t act right, and they don’t seem to think right. The same may especially be said about the Harfoots and their supposed goodness juxtaposed with their gleeful willingness to let anyone too slow be abandoned to certain death—granted, Harfoots technically aren’t hobbits, but everyone knows what they are a stand-in for. The point is, by redefining what an elf or hobbit is in Lord of the Rings as a universe, Rings of Power feels like a pale imitation rather than a fresh, new idea or a bold take.

A lot of people (particularly the writers, producers, and so forth in big studios) engaging with modern fantasy seem to really struggle with this—with understanding that identity matters. Boundaries matter. Definitions matter. Expectations matter. Once a story strays far enough from deep, established rules, it’s become an imitator of what it once was—or, rather than imitating, it becomes nothing. Or, worse than nothing, it becomes a reskinned version of how the creator sees our modern world.

Fantasy audiences don’t want the modern, “real” world when they turn to fiction. They want a different world, with different people, and meaningful rules and expectations. And when they turn to a specific world, they want that world, with all of its quirks and foibles. They don’t want the world shifted into an uncanny valley between generations.

Perhaps I get ahead of myself. There’s been a lot of talk going on about the… questionable art direction that Wizards of the Coast is rolling out for its latest “edition” of Dungeons and Dragons, which has put my mind on this topic. Here’s an example:

“Zero character.” Ouch.

When fiction loses its identity—it’s most important boundaries and definitions, it’s key limitations—it loses anything to say. And by that I’m not saying that fiction should be pushing a message or an agenda—almost all good stories do not do that, even when written by an author very impassioned about one thing or another. But they still have something to say. They still have energetic characters that want to come alive in your head, worlds that want to flourish in your heart, and they will move your emotions in meaningful ways. Stories with real identity are more likely to have enough depth that different readers will pull completely different things out of the story, entirely independent of any “message” the author may have had.

Dune is an example of well-defined science fiction—a story with a clear identity. You think of Dune, you think of spice. You think of shields (effectively personal force fields). You think of precognition. You are aware that laser guns exist, but also that they are nearly never used, and that the aforementioned shields have almost entirely eliminated the use of ranged/projectile weapons except in specific assassination efforts.

Speaking of assassinations, you also likely think of galaxy-spanning political intrigue when you think of Dune.

Dune would not be dune if any of these elements were removed, trivialized, or had their rules rewritten. Remove spice and you remove all need for the planet Arrakis—no one would fight over that desert hellhole. Remove shields and all weapons would become ranged again, and the Dune universe would start looking like any other sci-fi series. Etc, etc, etc.

Stories (and worlds) like Dune have enough nuance and depth to them that they talk, without having a particular message to push, because the point isn’t to push a message—and readers will get something out of the story anyway. Often something very different from what the author may have thought or felt. (Using Dune as an example, I think Frank Herbert is flat-out wrong about many of the things that he’s said about his own books. Paul Atreides is a hero in the first book, not a villain. Arrakis is not an chilling warning of ecological disaster—nature, through the sand worms, made Arrakis the way it was, a self-sustaining-though-harsh environment, and it was only through human intervention that the planet eventually became verdant. Get wrecked, Frank.)

Disney Star Wars is a good example of what happens when fiction loses its identity.

Look at the Force in the original trilogy—and even the prequels and some of the earlier television series—and you’ll see a power that, yes, can do some pretty crazy things, but is mostly very spiritual in nature. Sith can corrupt this spiritual power to do evil, but the natural, and most powerful, state of the Force is a quiet awareness coupled with a connection to… everything. This is part of why being inwardly balanced, achieving some sort of self-actualization is so important for Jedi to grow in their connection with the Force, and why the Sith physically decay because of their perverted, forced connection with the Force.

Modern Star Wars, on the other hand, makes Jedi pretty literally space wizards. Or maybe even space sorcerers, given how easily some modern Jedi grab onto the Force and do wild things with it without training or practice. The power has become so generic, so diluted, that it has no meaning anymore, nothing to say. The Force ceases to be a character, and thus ceases to be important or meaningful in any way. Without that spiritual element, Star Wars is left feeling like pretty generic science fiction.

Now, I want to loop back to what I said before. Do elves and hobbits have to be as Tolkien envisioned them? Does Dune have to have personal force fields, spice, and precognition? Does Star Wars have to have a spiritual, monk-esque component to the Force?

Yes. Yes, if the goal is to make a story within those respective universes that actually fits in the identity of those universes. Anything else is just wearing a skin, and poorly.

But no, the answer is “Not at all!” if you are creating something unique.

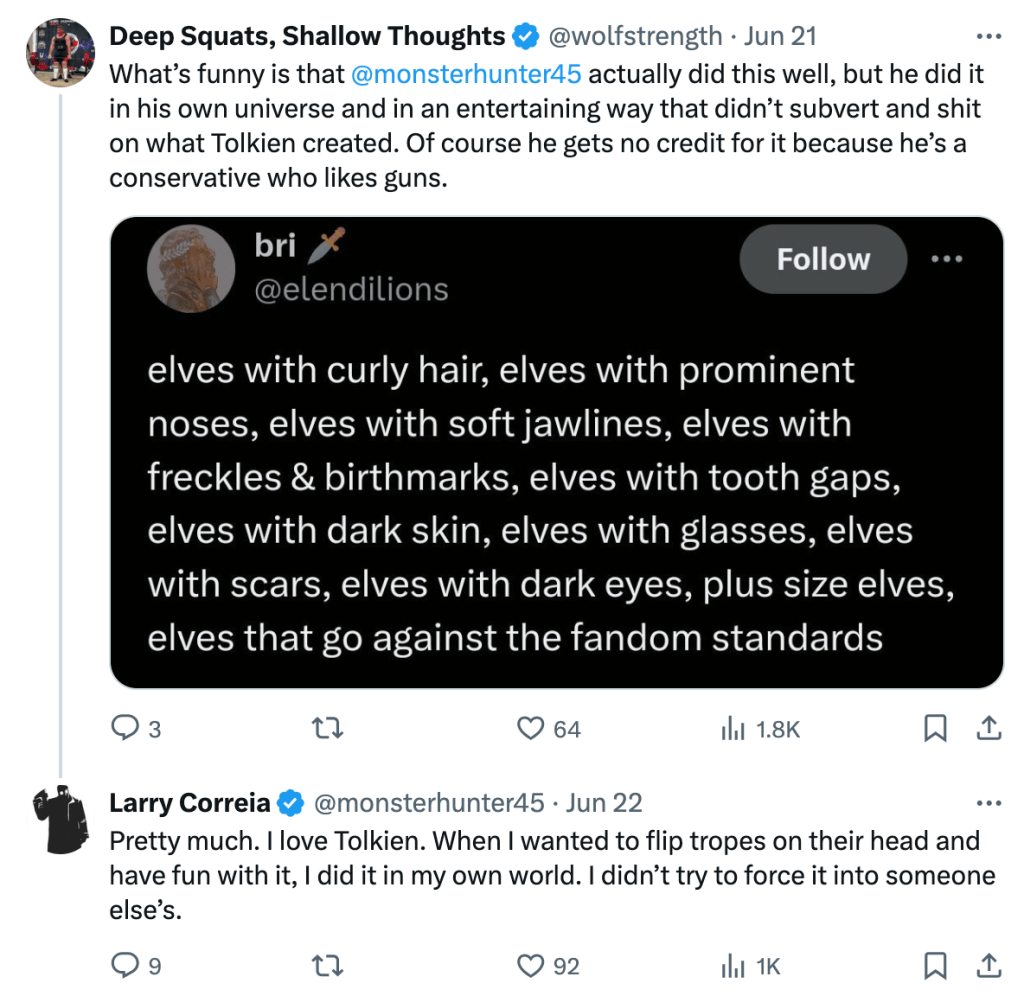

The elves in Larry Correia’s Monster Hunter International are trailer trash hicks. They are about as far from Tolkien as you can get. The orcs are metalheads that live in tribes and have a strong sense of honor—oh, and are also polygamists who are extremely dedicated to their families, also distinctly un-Tolkien. And it works. Well, it works marvelously well in Monster Hunter International, and it’s part of what gives that series its identity. Any version of Monster Hunter International—adaptation or sequel—would be irreparably damaged if elves and orcs were made any closer to Tolkien’s vision of those creatures.

Why do so many fantasy series, then, make the mistake of burning down their boundary markers, destroying their identities?

Good question. There’s probably a lot of answers, and it probably varies by author, studio, executive, producer, showrunner, screenwriter, actor, programmer, and so forth.

In my opinion, regardless of what else is involved, I do think we can find at least one common thread: a lack of confidence.

When a story is twisted into a perversion of itself—when its identity is replaced or warped to become something else—when a story really only carries the aesthetics of the universe it is placed in, but does not truly belong there—that, to me, suggests that whoever was in charge did not have confidence that the story they wanted to tell would survive on its own merit. The story could only, maybe, possibly, get an audience if Trojan Horse’d into another universe. But this usually backfires—at least with dedicated audiences. People who don’t know any better might enjoy these deviations, but the fans that gave the series life will revolt.

And I don’t think the new story would survive without those dedicated fans. After all, if the creators of the new story didn’t believe their ideas could survive on their own, I’m inclined to believe they are right. And if they can’t survive on their own, they won’t survive long coasting on the dwindling lifeblood and goodwill of an established franchise.

Writing Updates

Hazel Halfwhisker is moving along! As for the page count I’ve edited my way through, I’m in the upper 80s out of about 200 pages. Word count is going up, too, as I’m writing scenes that I previously didn’t know how to do. It feels really good to see this story coming together, but I’ve still got a long road ahead before it is finished. Still predicting the completed first draft will be around 200k, but naturally that’s going to need to be reduced a lot in future drafts.

Send-Off

This question might be a little weird—what are your two favorite wildly different versions of an idea?

Let me give you two examples, one specific and one broad.

Specific, I love the honor-bound, family-loving orcs in Monster Hunter International—and I also love the evil-by-nature orcs of Lord of the Rings. I would hate if the two crossed universes, but within their respective contexts I think they are amazing.

Broad, I love the two visions of the future in Theft of Fire and Blindsight. (Well, maybe I love to hate the future of Blindsight.) Both are near-ish future sci-fi with very distinct visions of what humanity’s future could be. Theft of Fire has clear faith in humanity—it does not shy from our ugly parts, but it also shows how human ingenuity, drive for creativity and freedom, and ability to become better ultimately prevails over greed and tyranny. Blindsight, on the other hand, seems to actively hate humanity, and seems to suggest that humans can only destroy or be destroyed—a message I disagree with and hate, but I enjoy how well Blindsight is done that I can’t help but enjoy the book anyway.

So, in that vein—what are your two favorite wildly different versions of an idea? And why do their unique contexts make them work?

Leave a comment