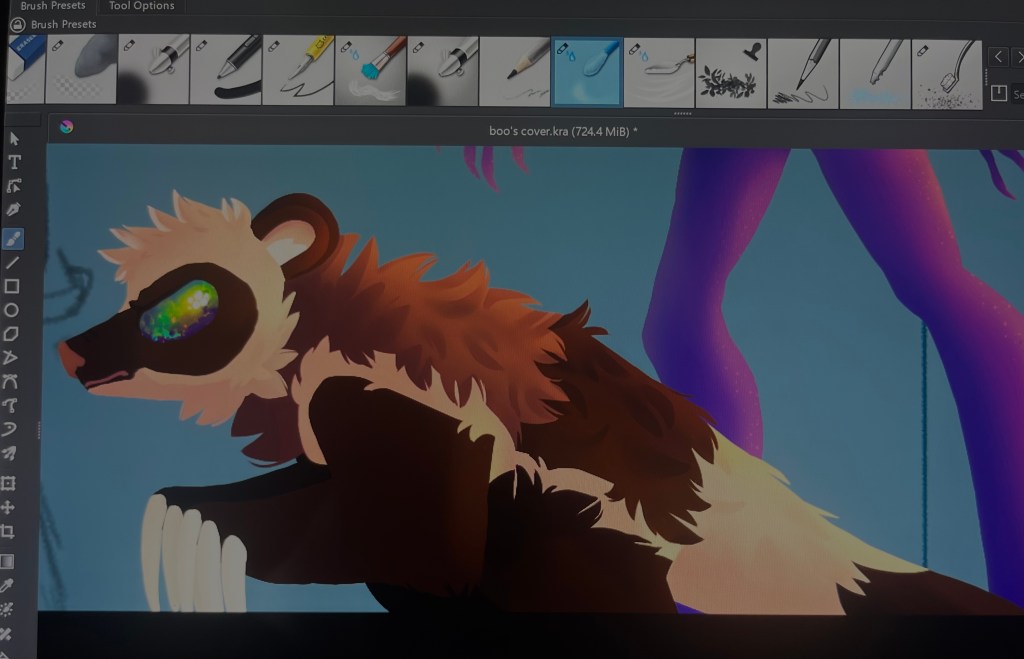

Look at that gorgeous little guy—I’m very excited for how the cover of Inner Demon is turning out. Kraw already comes through in the book so strongly, but now we also get images to do him justice! (As a reminder, you can read the prologue and chapter 1 here.)

Working with an artist and getting things right is a very fun process. I do not have a visual brain at all; using the following chart as an example, I’m a 4 on rare occasion, most of the time a 5:

My brain mostly works in terms of language and spacial awareness. Descriptions and words come to my mind when I imagine things, as well as a knowledge of their shape and size, texture and color, location, and so forth—but without “seeing” them. (Have you read The Goblin’s Puzzle, Andrew Chilton? I think it’s comparable to how the dragons in that book “see” the world.) As such, working with an artist to create an image of something I’ve invented on the page always results in me literally seeing something I made for the first time, and it’s pretty fun.

I’m also in the camp of authors who enjoy when artists put unique interpretations on things previously only represented in words, provided it stays true to the spirit of whatever is being visualized, of course. With Kraw above as an example—I think I only ever describe Kraw’s fur coat as shaggy and brown. Despite this, I think Eve’s addition of extra colors really works, in part because it is very true to real-world wolverines, one of the many inspirations that ultimately resulted in the kekeblin. The iridescent eyes with a shape kind of like a glare? I describe Kraw’s eyes as spheres, but this depiction still works because it catches his personality really well. I could come up with other examples of artistic license working within reasonable leeway, but you get the point.

If I ever am fortunate enough to have lots of fan art of my work, I hope each piece is able to be recognizable to a character or concept while still being its own thing, distinct from the rest in details and style. After all, everyone who reads the book will come up with their own distinct mental image of the world and characters, despite reading the same words, so variety in art captures reader experience better than keeping everything same-y anyway.

Will this change how I describe the character in-universe? Of course not. I’ve got my preferred way of imagining and describing things, and it wouldn’t be my world otherwise. But co-creation is a vital part of creative endeavors. (I might get a little more creative in the fur colors of future kekeblin characters, however.)

Here’s the whole, in its current state. There’s still a lot to do, but it’s turning out nicely!

Anyway… Here’s how my writing projects have been going!

- Halfwhisker has not seen any progress, beyond consolidating some more notes and tweaking more outlines. I don’t expect to begin draft 2 in earnest earlier than halfway through April.

- Inner Demon has fourteen chapters recorded—not quite halfway there, but making good progress. That, plus the cover updates already mentioned. We’re in a very slow-but-steady stage.

- The Courage in a Small Heart graphic novel adaptation… is finished! Well, draft 1 of the script is finished; since I’m adapting a short story that’s already in final draft, I doubt that I will tweak draft 1 much, if at all. But once I actually start working with an artist, I could see more things changing if it results in a better overall adaptation. (After all, visual adaptations need to lean into the strengths of visual media, while the original written stories have their own strengths.)

Discussions—Making Audiobooks

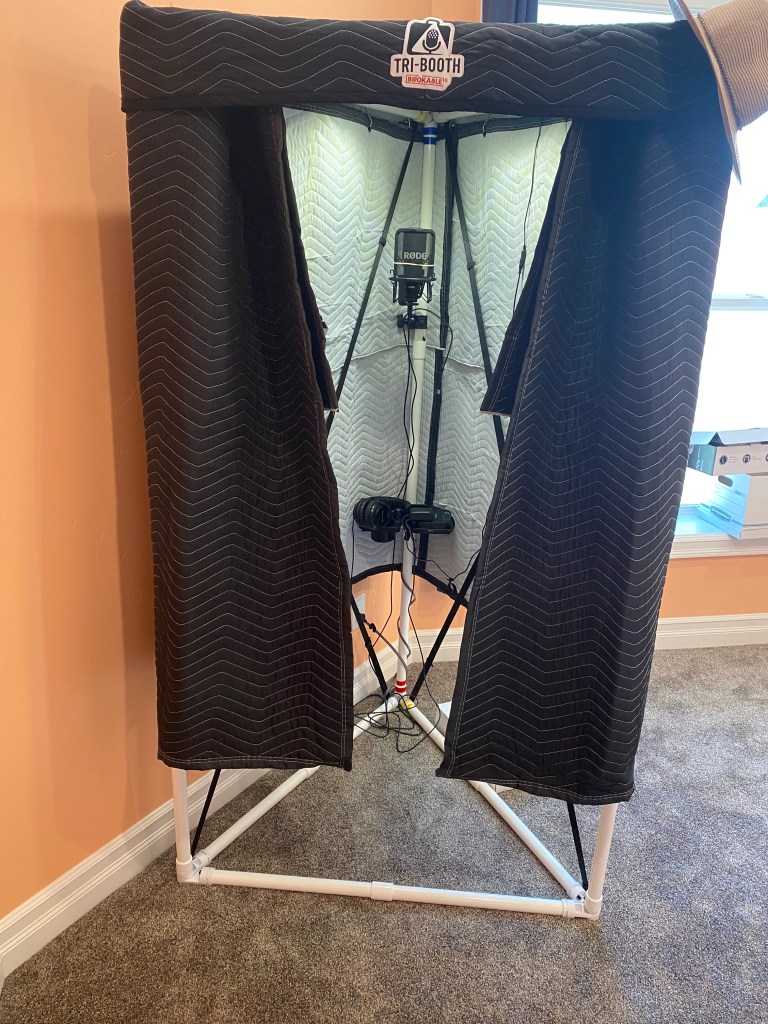

Here is my audio recording setup!

I use a Tri-Booth portable recording booth with a RØDE USB microphone and record the book myself. I use TwistedWave as the recording app on my laptop. It’s all set up in my at-home office. I hire my brother-in-law, an audio engineer, to do finalize the files after I record them.

This setup is a little heavier in the initial investment cost than I would have liked, but the good news is that as long as nothing breaks I’ll never have to pay another cent to make an audiobook again (except for hiring an audio engineer). It also gives me full ability to release my audiobook very close to print and ebook release—although I intentionally stagger things just a little, for a variety of reasons.

In general, this setup gives me a lot of direct control that I wouldn’t have otherwise. There’s a lot of upsides to this home-done approach.

The downsides of this setup? Well, as I mentioned, initial investment isn’t cheap, and hiring an audio engineer isn’t free—but I value the time I save for working on new projects more than the cost of having someone else work their expertise in an area I’d need significant practice in just to be competent. It does take a while to record an audiobook (with my schedule), time I can’t spend writing a new story, but that’s another price to pay.

Why do I bring this up? Well, audiobooks are a big market, and there are a lot of readers (listeners?) who only consume books in audio form. As an indie author trying to cast my net as wide as possible, it just made sense for me to try and get all of my books in audio. A lot of other indie authors are in a similar boat as far as desires are concerned, but not sure what to do. Well… here you go! At least, my solution is one way to do it.

If this doesn’t interest you, for whatever reason, here are other options you could consider researching:

- Audiobook Companies: Kind of like querying for a publisher, you can query companies that solely produce audiobooks. (And, just like with publishers, know it’s probably a scam if they make you pay them up-front, unless you sign a contract where their only compensation will be what you pay them, not a percentage of royalties.)

- The advantages? If it’s a good company, they handle everything a publisher is supposed to handle, from finding voice talent to recording to advertisement.

- The disadvantages? You give up a lot of creative control and your royalties are a much smaller percentage of what they otherwise would have been.

- Revenue Sharing: ACX/Audible/Amazon and Findaway Voices both have similar programs that help authors on tight budgets get connected with voice actors and make audiobooks. The gist of it: through the respective marketplace, you are assisted in finding a willing voice actor and sign a contract with him/her that gives him/her X% of your book’s revenue for X years, but you pay little or nothing up front. (I think, as part of this deal, it’s specified that the voice actor will provide you with final files, so you won’t need to then hire an audio engineer. I think.)

- The advantages? Low initial investment, and, rather than recording yourself, you work with a professional voice actor—or (more likely) an aspiring professional voice actor.

- The disadvantages? Well, it’s my understanding that most voice actors who take deals like this are inexperienced and/or looking to build out their portfolio, so there’s a bit of a risk in that they won’t have a proven track record. You also will make a smaller royalty on your audiobooks, and (most of the time) you will only be able to sell your audiobook exclusively on the marketplace that provided this service. At least, until the contract runs its course.

- Crowdfunding: I know of at least one very successful crowdfunding project that allowed the author to hire multiple voice actors for his novel, as well as an audio engineer, and have small immersion sounds added to his audiobook. The project? The Theft of Fire Audiobook! (Note that this campaign ended quite some time ago.)

- The advantages? If you like doing things yourself, this is probably the ideal situation, because you have control over everything.

- The disadvantages? Good luck crowdfunding enough money to do a high-quality audiobook with even one hired voice actor, unless you already have a large following (or are willing to spend the cash out of pocket).

Discussions—Uninclusive, Uninviting, Insensitive, Unkind (is the Ideal)

I noticed when looking at my analytics that one of my most-viewed posts is the one with the above-mentioned name, which I found rather interesting. In terms of internet timelines, it’s ancient. I doubt my quick, nostalgic reviews of various TTRPGs that I’ve enjoyed are the reason people are looking up that post.

Could it be… the rage-bait title? I imagine that’s a more likely explanation than anything else.

It’s only half-rage-bait, though. I stand by everything I said. “Sensitivity,” in its modern incarnation, is a tool for the eternally offended to exercise tyranny over everyone else and ought to be firmly rejected. It’s closely related to various other forms of cultural marxism, which have the same ultimate goal of forcing people to think in specific, destructive ways.

Maybe better said: never be afraid to be risk offense. That’s the only way to maintain freedom of thought. Tactfully judge for right situations, of course, but know that someone taking offense to something does not immediately mean they are right for being offended or you are wrong for risking offense.

(As an aside, doing what’s right sometimes requires offending others. Taking offense is most often abused as the tool of those in the wrong in some fashion.)

The ability to be offensive is critically important to the health of a society.

Now, first, I’m going to attempt to define what I mean, in this instance, by “offensive”: in other words, the “offensive” includes things people (no particular “people” in mind, just anyone) don’t like, might consider hurtful, or might want to outlaw entirely. The “offensive” might include the crude, obscene, or objectionable at times, but “positive offensive” (meaning, creating some positive outcome) doesn’t exist solely on the level of the crude, obscene, or objectionable—it may make intelligent use of such things for a purpose, but might be offensive for entirely unrelated reasons.

In my original post I focused on TTRPGs and how ridiculous it was to direct players to play in certain ways based on sensitivities real-world people might have, but this applies to all aspects of life. The ability to risk offense is perhaps the keystone of free speech and freedom of thought. It’s a key part of being able to criticize government leaders, laws and legal practices, social customs, groups and activities we don’t like, and so forth. It’s part of the social brainstorming that brings about positive (and negative) change, or that can even be used to reinforce what’s already good and working. Removing even a part of the ability to risk offense is a rejection of free speech and free thought.

Yes, yes, that doesn’t mean total anarchy is the way—if there’s ever an episode of Bluey that features explicit nudity (well, human nudity—I suppose the dogs are always naked, despite all the laundry they do), as a children’s show that’s just being crude and obscene and rightly ought to be censored. There are certain things that, in public spaces, are beyond the pale—such as explicit nudity or explicit depictions of violence. It can be a difficult balance to strike, but it’s better to err on the side of more freedom than less, I think.

As well, regular exposure to the “offensive” is good for one’s emotional health. It lets you build up resistances and immunities, on an individual level and a cultural and social level. Even children need a certain degree of exposure to the “offensive,” an idea that I think is best captured in this G.K. Chesterton quote:

Fairy tales do not tell children the dragons exist. Children already know that dragons exist. Fairy tales tell children the dragons can be killed. [Emphasis added.]

In fact, that general idea might catch what I’m trying to say best, this elusive idea that certain types of offensive is good for us—even scary stories that risk keeping children up at night.

I think such things are equally important for adults. Adults, even more than children, see the “rot, darkness, and death” of life and need to be reminded that they have the power to drive it back “by sword, spell, and flame.” Fiction is one of the sources by which we do this, which then spills into culture and society, politics, and so forth. By creatively constructing evil (one of the “offensive”), then seeing it defeated, we (in a manner some think paradoxical) bring more light, hope, and strength into the world.

I don’t blame modern pessimism entirely on modern storytelling, but I do think mainstream storytelling erring toward grim stories, grey stories, stories with no heroes and usually only lesser evils, has absolutely contributed toward how darkly most people see life. These are portrayals of the offensive in the wrong way—to wallow in it, like a pig in mud. Yes, there are things wrong with our modern world, but we ought to have hope that things can be made better, and we ought to reinforce that hope in our art.

And, yes, that means the “offensive” must be able to include jokes that certain people might not appreciate—that might even be at their expense. (I don’t think it’s a coincidence that racist jokes are very popular among mixed crowds with the lowest racial tensions, but are heresy among crowds with high racial tensions; the ability to make such. jokes is a kind of canary in the coal mine.) It also means stories must be able to include charged topics. But, I think, even more important, it means stories and art need to be able to break away from our world, either to provide us an escape or to show us that, yes, things can be much worse—but can also be made better.

That’s one of the issues with people who view all art as political, or expect all art to be a dissertation on whatever is the political topic of the moment. That’s a restriction of thought, and a sign that the people who push such things have no creativity or hope.

We ought not to live in sanitized worlds. Stories need villains—and genuinely evil villains, ones worth of defeat. Or, at least, true, gross opposition. This applies to children as well as adults. Sanitized stories lead to sanitized minds, destroying mental and emotional immune systems, all but guaranteeing total system shock (and eventual failure) once that individual is exposed to the real world.

Sanitizing—entirely removing the offensive—is also a form of lying. Real life is offensive. One of the responsibilities of the individual in the real world is to manage his or her own emotional resilience, and not offload that to a neighbor.

The offensive can reveal our foibles, often in a humorous light, making it easier for us to fix them, or at least not make mountains out of molehills.

Of course, there still are specific places with specific purposes where it’s perfectly acceptable to control what types of “offensive” are present and aren’t. The home, guided by caring parents, is the perfect example. Parents ought to define what content is and isn’t acceptable within their home, and then enforce those limits. As mentioned before, it’s reasonable for certain extremes to be banned from public spaces so as to protect those who would be harmed by such things—like children.

All of this isn’t particularly specific because I’m trying—but not strictly succeeding, I imagine—in avoiding getting political, or advocating for a particular policy. It’s also why there are so many closely related topics I’ve only barely touched on, or neglected to mention at all. I want to focus mostly on books and entertainment in this blog, after all. But art still has meaningful purpose—culture, social, and personal values are often the deep weavings of art, which then gets passed down to those who partake.

As such, we ought to take art seriously. Seriously enough to enjoy it. Seriously enough to laugh at off-color things. Seriously enough to find artists that we trust to portray the offensive well.

Well, I’m done for today.

Leave a comment