Get yourselves settled in for a long one. After I provide my writing updates, I’ve got a review for After Moses: Prodigal in the pipeline, musings on deathbed repentance as a story element (I hate it), and I’m entering into conversation with two other blogs on articles/essays they’ve posted.

Yeah, I know, insane. I disappear for a month at a time, then I post two long ones in less than half a month. When it rains it pours, I guess.

—

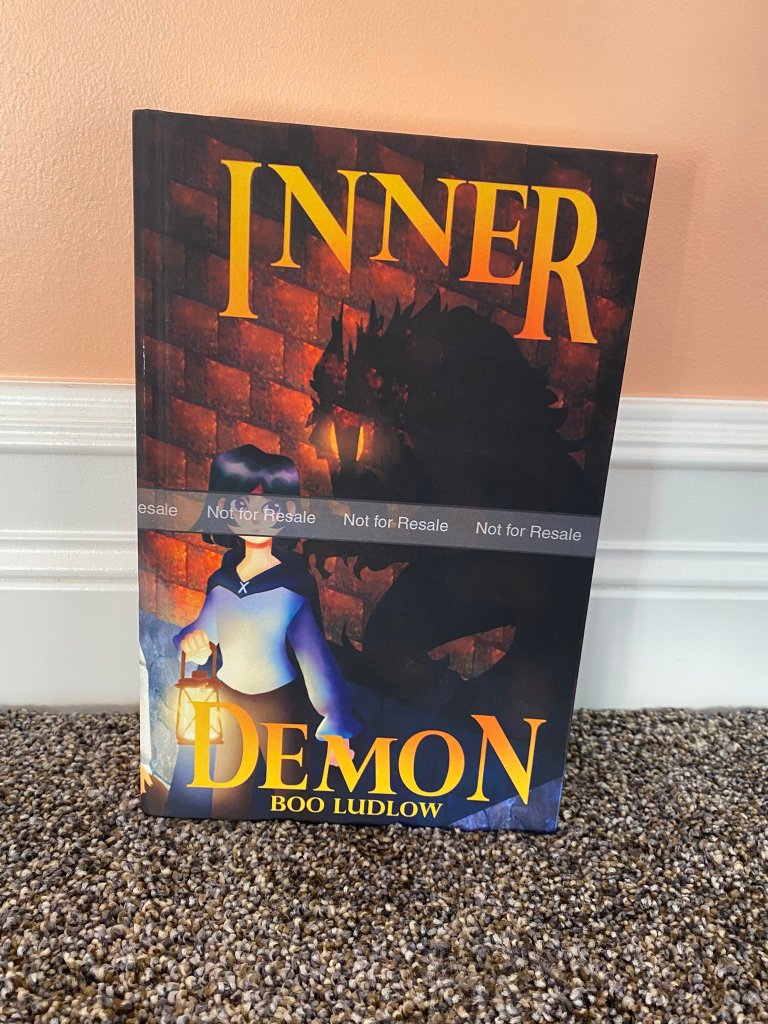

The proof copies for Inner Demon are in! Woohoo! Here’s what the hardcover looks like:

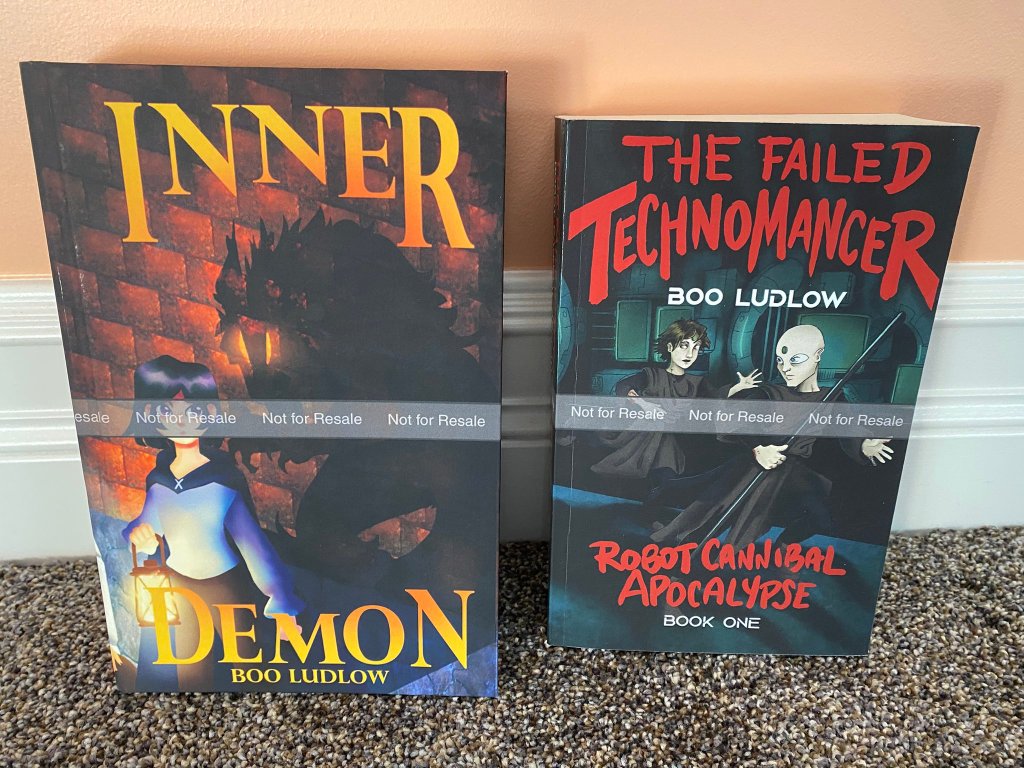

The paperback wasn’t meaningfully different in appearance, so I left it out. I also put the hardcover proof next to The Failed Technomancer in that last image for size comparison—I couldn’t do hardcover unless I made the book bigger, so I went that direction.

I’m pretty pleased with how it turned out… overall. Largely. I like it, and I want to like it. I have a few things to keep working on with the artist. Something about the image is… grainy. That’s not actually the right word, but I don’t have a better one at this moment. And I’m not sure if that visual issue is because of the image file—which looked clear on my computer—or the relative quality of print-on-demand.

Covers are so important and so tricky.

Also, the ebook is up for preorder. Apparently Amazon doesn’t let you set up ebooks and let them sit in a “waiting for publication” status, like you can with paperbacks and hardcovers; you have to put them on pre-order. So… here’s the pre-order link! Have no fear: the final manuscript is submitted, and what should be the final cover is submitted, so you will have a final-draft-book on your Kindle if you preorder, even though I’m going to continue to tweak things behind the scenes (and update the publication date once a few more things come together).

As for work on Halfwhisker, I’m far slower than I ought to be. What I should be doing is skimming each scene, making a one-sentence summary of the most important events in said scene, and also making notes on the number of beats in the scene with one-sentence summaries. That will help me to be more purposeful when I go in and start serious revision. Instead, I read way too deeply on the first two scenes, making probably unnecessary line and copy edits in the process. Gotta be more disciplined as I approach further edits this week.

Another part of the reason I’m slower than I ought to be on Halfwhisker revisions is because I’m working on revamping the website. No promises for a quick update, and no promises I won’t break everything—I’m treading in very unfamiliar waters here—but hopefully the end result is a vastly improved experience for all involved.

Bloggyness Review—After Moses: Prodigal

Recently I reviewed the indie novel After Moses (Michael F Kane); I was so impressed by the novel that I immediately went out and bought the rest of the published series, and I’m excited for when Kane publishes the sixth and final After Moses novel later this year.

Once again, I return to you with a strong recommendation. After Moses: Prodigal did an excellent job at taking the foundation laid out in After Moses and building on it. In this novel, Matthew and his ragtag crew of freelancers must head to the moon Ceres for a handful of jobs that, assuming everything goes well, will allow them to be in and out in just a few days. No one particularly wants to be there: Matthew is primarily here at the behest of his arch-nemesis, Whittaker; Ceres is the home of the criminal syndicate with a million-dollar bounty on Yvonne’s head; and Grace and Davey were once street urchins deep in the ghettos of Ceres. In short, it’s a situation ripe for everything to go wrong and a lot of history to be dug up, and you can bet your trusty revolver that’s exactly what happens, beginning with Grace disappearing.

Prodigal does something risky by splitting up its characters early on and frequently. Most of the time they travel in duos, so you still get plenty of interesting character interaction; but the number of ways the characters are paired off and remain compelling, in addition to how well a specific character carried various chapters despite being entirely separated from the main group, is a testament to just how well Kane has built up and fleshed out the main cast of After Moses. I genuinely loved each character and felt agony for them when they suffered. (And believe me, all of them have their feet put to the fire in Prodigal.)

If I had any criticisms for Prodigal, they are the same nit picks that I had for After Moses: the book has some occasionally painful spelling errors and I’m not a huge fan of the formatting. Neither are deal-breakers, particularly considering how strong Kane’s writing is, and I stopped noticing the formatting weirdness before too long, as well as most of the copyediting issues.

I don’t want to end this review on those two downers, so I just want to emphasize how excellent Kane’s character work is. Two scenes in particular come to mind: a moment of heartache shared between Matthew and Davey after days have passed in their unsuccessful hunt for Grace, a lowering of guards that struck me to the core; and an extended flashback that made one particular character feel as familiar and precious to me as the rest of Matthew Cole’s crew.

—

As an addendum, I’ve nearly finished After Moses: Wormwood since starting this blog post, and it’s also excellent and continues to explore new ground. In it, Cole and his crew need to help prevent humanity’s expedited extinction at the hands of Abrogationist terrorist Logan Alexander. Really heartfelt. Really impressive how Kane pulls together bit characters in previous novels in meaningful ways in this one. The backstories are a little heavier in this book than Prodigal, but they still largely worked for me. Another strong recommendation!

Also, if you want to check out After Moses, I recommend purchasing the ebooks directly from Kane’s website. I’m not getting paid or sponsored to say this—it’s just a better deal. It’s the same price as on Amazon, but if you buy the ebook on Amazon you don’t own it: Amazon won’t let you download the file for use outside of the Kindle ecosystem, and Amazon retains the right to take the ebook away from you whenever the megacorp wants. If you buy it directly from Kane, you get the ebook DRM-free, meaning it fully belongs to you to do whatever you want with, period. Also, Kane gets paid a bigger percentage of the sale than he would if he sold the book on Amazon, which makes it easier for him to finance spending more time writing more excellent books for you to read. Everyone wins!

(I’d like to set up my own direct shop eventually—other than the effort of drawing people to it, it seems far superior to most other avenues for selling books.)

Discussions—Deathbed Repentance

Speaking of Prodigal… a quote from that book reminded me just how much I hate deathbed repentance. Matthew Cole says this after a newer member of his crew offers to sacrifice himself to make up for mistakes that he’s made:

We don’t make our own atonement… A good deed, even a sacrificial one, doesn’t make up for the mistakes of a lifetime. So go ahead and wipe that notion out of your head. You’re not here because we expect you to make things right. You can’t do that. You’re here because of Grace. She wants you here. Evil deeds aren’t covered by good ones, they’re covered by heroics.

(Two notes for clarity: if it’s not obvious from the context, “Grace,” above, is another character’s name, not the concept. Also, I distinctly remembered the last word of this quote being forgiveness, but the word I had recorded was heroics. Being that trolling through an ebook on a Kindle for a specific phrase is a miserable, largely futile effort, I trusted my notes and will rely on Mr. Kane’s forgiveness if I’ve misrecorded his work.)

I love this quote. And I especially love the story behind this quote. In short, a character—I’ll keep light on the details to avoid spoilers—has, through cowardice, allowed evil to proliferate under his watch his entire life. Later in the story someone needs to do something incredibly dangerous that, most likely, will result in death, and this character sees this as an opportunity to make up for a lifetime of failure—but he’s told, to paraphrase, “Hell no, you’re not killing yourself now that you’ve just started making the right decisions,” and then Cole gives the little speech above. It was an exceptionally satisfying twist, particularly when I had spent several pages figuring that a deathbed repentance (or some other character sacrifice) was coming and not looking forward to it.

I think that deathbed repentance is a trope that weakens stories, and here’s why. Deathbed repentance is a fundamentally selfish gesture on a character level—and thus contradictory with the what most writers want to accomplish with a deathbed repentance—and makes for unsatisfying storytelling; I can’t think of a single example where it improves the overall story.

As far as selfishness is concerned, deathbed repentance is the easy way out. The least sincere. The path of least resistance. It leaves everyone else to clean up the mess while the dying character gets a get-out-of-jail free card, essentially. It often comes with a forced expectation that the dying character should be deeply appreciated, for some reason, which is manipulative; it also carries the inherent assumption that one “good” act undoes a lifetime of doing ill, which is just plain false. In short, it’s a way for a character to try and force all of the reward for being “good” without actually putting in the work.

As far as the craft of storytelling is concerned, death isn’t very often satisfying. After all, death takes a character out of the story, permanently (depending on the genre), leaving that character uninvolved in what comes next. Often the most compelling parts of a story are the journeys of growth the characters have!

When death IS satisfying in a story, it’s usually as a conclusion to an arc—which deathbed repentances still handle poorly. After all, if the character’s movement is largely (or entirely) downward, a last-minute shift upward is, at best, jarring; when put in context with the character’s overall movement, it’s a meaningless blip that does nothing to discredit the likelihood that the character would go right back to his old ways if given the opportunity.

Rather than dying, it would always be far more compelling to have the penitent character confront the consequences of his actions, apologize and show genuine remorse, and do all within his power to make things right—and then, if it would be a satisfying conclusion, die. (But after seeing the character grow and change, we might want him to live.) Some things may be impossible to make right, but wrestling with such conundrums (through natural character growth, not as a sermon) can make for the most powerful storytelling.

In short, what we want to see in storytelling is, generally speaking, the struggle of characters progressing or regressing, and then fitting conclusions to character arcs. So do that.

Now, deathbed repentances normally happen at the end of stories, when there isn’t time to have a journey of struggle for growth, so I understand why some writers choose to give a character a lazy arc conclusion, or a forced moral heel-turn; all the same, I think it’s far more interesting, and satisfying, to set a penitent character on the path to redemption, a journey which the reader can imagine or which may be fulfilled in a future story.

Two examples come to my mind, one a lot more famous than the other.

I don’t find Vader killing Palpatine and then dying satisfying in the slightest. It’s the weakest part of the Skywalker story (ignoring the trilogy later grafted on to an otherwise complete and satisfying duology of trilogies; more on that later); supposedly Anakin fulfills the prophesy to bring balance to the Force by killing Palpatine, and many interpret that as being fulfilled through the death of such a powerful Sith Lord, end statement—but what is actually fixed? All of the terrible evil that Vader has committed over the course of his life is still unaddressed. The Galactic Empire, with all of its evils, still exists—even if the empire for some reason won’t survive the death of its emperor, it’s unlikely the fractured pieces the empire breaks into will be significant improvements.

Luke gets to be a good person for forgiving his absent and villainous father, the bad guys die… For some reason the narrative tries to justify that Anakin is good and purified now, despite the objective evidence of the prequel trilogy that Anakin, despite making the right moves on occasion, slips back into selfishness and hate with remarkable ease. This is just a continuation of that cycle.

You want to know what would be significantly more compelling, challenging, and interesting? Vader surviving and having to make good on his “coming to Jesus.” He now has to take command of the Galactic Empire and somehow steer it in a more benevolent direction. He has to struggle with the anger and hate that he feels, that is habitually a part of his life, and learn not to Force Choke to death anyone that slightly annoys him. He’d be so wrapped up in fixing the litany of mistakes he’d made over the course of his life that Luke could still go off and have adventures of his own in the Extended Universe.

And, of course, Vader would have to come to grips with the fact that he could never fix most of the mistakes he had made. That it’s unlikely he would ever get forgiveness for most of them, at least not from those directly affected by his wrongdoing. He’d have to figure out how to struggle forward anyway. It would be… weirdly inspiring.

The second example that comes to my mind I like even less:

In the first Puss in Boots movie, Humpty Dumpty is the villain. He causes all sorts of harm before the movie begins, and during the course of it, and then near the end he does one good thing and falls to his death… and it turns out there was a literal golden egg inside of him all along. For some reason this leads Puss to conclude that he always knew Dumpty was always good, in spite of everything.

No. This is extremely unsatisfying. Good people aren’t perfect, but they consistently do good things among their (sometimes many and grievous) mistakes, and generally strive to fix those mistakes. Bad people consistently do bad things among their (if any) good-appearing deeds, and rarely, if ever, attempt to repair mistakes. Yes, some people are complicated and nuanced, but that doesn’t justify calling good evil or evil good; it also doesn’t justify Puss instantly changing his judgements of Humpty Dumpty.

Similar to Vader, Dumpty having to confront his wrongs and show that he wanted to change and was willing to put forth the effort would have been far more interesting and compelling, even if the story ended by putting him on the beginning of that arc rather than actually playing it out. If nothing else, he should need to work to earn Puss’s trust and respect.

Don’t believe me that this is the best way to handle a penitent character?

Without question, Zuko is one of the most popular characters in Avatar: The Last Airbender, and I think that can be directly attributed to his excellent character growth. He began as a bitter, angry, self-centered, violent young man who wanted nothing more than what he thought was honor, but over the course of the series grew into a noble and admirable man. Lazier writers might have kept Zuko as an antagonist the entire time, perhaps with moments of reflection that left us wondering if there was still good in him, and then had him make a heroic sacrifice at the very end to ensure Aang’s victory. Imagine how much would have been lost if that had been the Zuko we were given!

Of course, Zuko’s change began far before the last episode of the series, but deathbed repentances don’t always happen in final arcs, so I think his example is still fitting.

This is also all not to say that characters should never have last-minute changes of hearts—it’s a tool that some writers can use to good effect, and that can be built to in satisfying ways. The issue is when the narrative around such an action seems to reward that deathbed repentance as being equivalent to the journey and growth of all the other characters up to this point. There’s no weight behind such a claim.

Discussions—Conclusions, Canon, and Reader Responsibility

You don’t hate The Rings of Power or The Last Jedi or The Wheel of Time [Amazon] series because they aren’t as good as the original. You hate them because they try to tell a story whose soul they don’t merely misunderstand but that they actively repudiate.

As recipients of such stories it is part of our duty as stewards to reject bad story: to call out narratives that breach the bounds of truth or violate the premise of the larger whole. Not just as passive consumers but as active custodians of the inheritance of literary excellence that has been passed down to us so that we can in turn hand off what is excellent in our time to those who come after us.

The above quote is from “Inheritance Squandered: The Parable of Prodigal Storytellers“, the author of which goes by “Marlin“. Per the usual, I recommend going and reading it, although this is a much longer one than the last one I shared. Here’s the gist of what I got out of the essay: endings matter and beginnings matter. That’s pretty simple and, I think, inarguable. How a story ends can completely make or break everything that came before it, potentially taking flaws and making them part of a greater whole or taking prior excellence and utterly ruining it (looking at you, Game of Thrones); how a story begins sets the foundation for what’s possible and what’s satisfying. Pretty basic stuff.

I also agree with his ideas of reader responsibility, that we ought to do what we can to “[be] active custodians of the inheritance of literary excellence that has been passed down to us so that we can in turn hand off what is excellent in our time to those who come after us.” In fact, I think his arguments go well with some things I wrote about previously in the context of Dungeons and Dragons (Discussions—Letting Go)—specifically, I said:

First, the things you love can never be destroyed—not unless your memory utterly fails you, anyway, and[,] unless they are completely wiped out of existence[,] you can continue to interact with them in the forms you most appreciate.

My above point was that it really doesn’t matter how much modern companies abuse the stories and worlds I love; I still have the originals. The Lord of the Rings, The Hobbit, Watership Down, Star Wars, every Disney remake, and others fall cleanly into this category; in my house, in my conversation, everywhere that I have influence, on my shelf in physical form (physical media is always superior), the good in these stories will live forever, while the poor adaptations or follow-ups will be forgotten—except, perhaps, in lesson or as cautionary tales.

Marlin did bring up two examples that complicate matters, and those are the resounding duds of Game of Thrones and His Dark Materials. Both were ruined by their conclusions and are examples that, unfortunately, the things you love can be destroyed, at least if you fell in love with them while they were yet unfinished.

Unfinished.

And that’s why I disagree with his analysis of Star Wars in his sub-sections Case 1 and Stories Can Be Broken from the Start.

I agree with Marlin that the sequel trilogy undermines the foundation of the prior two Star Wars trilogies and, when viewed through the lens of the sequel trilogy, ruin Star Wars by making all that was previously won meaningless. I also agree that elements of the prequel trilogy weaken the original trilogy, such as the actual nature of the Clone Wars, when, again, viewed through the lens of the prequel trilogy.

But… so what? The original Star Wars trilogy is a complete story. If there had never been any Star Wars media after Return of the Jedi, we still would have had an excellent, satisfying beginning, middle, and end, a whole greater than the sum of its parts. In short, the original trilogy is complete; those who want more Star Wars may go seek it out, but no one needs it to finish the story. Therefore, you can choose to reject additional material without any complications.

I think this applies to Marlin’s analysis of Star Trek as well. Why should I care that Discovery and Picard are terrible? I won’t watch them, and I won’t share them with people. Each series that came before is complete on its own and doesn’t need these follow-ups. The follow-ups only exist on life support as long as big companies use them to burn money; they will be forgotten almost exactly when corporate cuts off access to the bank account.

That is all not to say that poor stewardship shouldn’t be frustrating. It is. In fact, I think it’s justifiable to hate story additions that try to dismantle all that came before—or are simply poorly done. But we’re getting this backwards. Exhuming a completed story to staple on a poor prequel or sequel doesn’t ruin the original story if you don’t let it; you choose what to focus on and breathe life into, not the hacks hijacking the work of far greater men and women.

After all, these new stories only have life as long as we give them attention. Those people who want to destroy good literature only “win” when we let them—when we give up and say that something we love was “destroyed” and abandon it. When we allow ourselves to forget what they have chosen to destroy.

The power is yours. In your head, in your heart, you choose what gets to stay and what gets weeded out. And you have influence in whatever spheres you call your own to do the same. What you talk about. What you share with others. What you pass down. How you do these things. It’s your responsibility to take what’s great in literature and pass it on, and allow the rest to die either ignominiously or as critical examples of failings past.

Perhaps what I’m suggesting is radical. But since stories have always been given life by those who read and love them, I don’t think it’s unreasonable.

Discussions—”New” Fiction

I’ve shared a few articles from MS Olney before. The following, “We’re already writing the new stories you’re asking for“, is a response to a Not the Bee article arguing that, with mainstream art and culture dying, something new needs to be made to take its place. Olney rightly points out that’s already been happening, and has been happening for decades in indie spheres. Unfortunately, a lot of people who hate the stories being put out by mainstream publishers and filmmakers haven’t put forth the work to discover these new stories; they are undermining themselves by not shining spotlights on these new stories.

Another artist by the name of George Alexopoulos regularly points out similar things. Many moderates, conservatives, and libertarians like to loudly complain about the state of culture, but seem unwilling to support the artists actually trying to make a difference—neither providing attention nor financial patronage. Culture is downstream of art; without supporting artists, there will be no change to culture.

Yes, there are other things that need to be changed, too. But if liberty-, conservative-, or common-sense-minded people don’t show up to the culture war at all, they have no right to complain when they lose.

I’m not stating anything revolutionary here, but just doing what I can to hold up the torch. After all, if you find yourself floating down a rough river going where you don’t want to be, sitting back won’t fix anything; you have to pick up the paddle and stick it in the water to at least start trying to control your movement.

—

That’s all I had to say this post. Subscribe to get an alert whenever a new blog post goes live. It’s the best way to keep up with my upcoming writing projects, as well as thought-provoking discussions like the above. And feel free to leave a comment if anything here made you think.

Leave a comment