No, this blog post isn’t about the Kafka novel—this blog post is primarily about me, with a lot of thoughts inspired by Kristin McTiernan’s Substack post Talent Isn’t Enough (And It Never Was).

Today, I’m discussing on the process of turning into a real author.

What’s an Author? (No Seriously)

First of all, I should define what it means to be a “real” author for me.

As far as most people are concerned, if you have successfully written a book in some form and then published it, you count as an author. This definition is very literally accurate, but it’s not specific—it includes a wide spectrum of authors ranging from one-offs and hobbyists to people whose primary income is derived from their writing (and related endeavors).1

I want to be in that latter category. If I want to meet my goals and dreams, success (and success as an author) requires me to, eventually, be able to quit my day job and write full-time.

Perhaps this could be defined as being a professional author. For me, for my life, that’s real authorship.

Some Hard Lessons Learned

Once upon a time I thought I would become a professional author through the fairy tale that many authors assume to be reality. In other words, I thought I would find an agent (with some effort, but not before too long), that agent would connect me with an editor and a publisher, and that the agent and publisher would perform all of the business and marketing side of the job while I focused on writing full-time. I figured I would still need to keep my day job for a while, but that my time in the sun would come, so to speak.

After all, I was working full-time. Even if I wanted to learn the business side of being an author, where would I find the time? Offloading all that extra stuff to someone else just made sense.

Well, I was even more naive back then than I am now.

Waking up was a gradual process for me—I never had a lightbulb moment where I suddenly realized that traditional publishing is not the future, nor where I realized the amount of effort it would take to accomplish my goals through indie publishing. (Spoiler alert: it hasn’t happened yet, but I haven’t given up.) But I had a lot of eye-opening experiences along the way, paired with many uncomfortable lessons. If you just want a bullet-point summary, skim through the bolded sentences below, but I think there’s a lot of useful stuff in here for an aspiring author with goals similar to mine.

Writing and publishing a book is damn hard. Even finishing the first draft of a short novel takes most people significant time and dedication, and that’s to say nothing of revising and editing (if you’re wise enough to do so) and then learning how to either traditionally publish or self-publish. And I say learn because no part of the process is obvious and there’s a lot of things you’re likely to be terrible at, or just not know, early on.

A manuscript is one thing, but a book is something else entirely—to say nothing of actually getting that book into people’s hands!

For those going the traditional route, finding and capturing an agent is an art, but only to those who know how to find the right agents for them and who know how to craft effective query letters; for everyone else, it’s like trying to hit a bullseye while blindfolded and after being spun around a few times.2 For the independently-minded—well, I can’t speak for everyone, but I had no idea how to turn a completed manuscript into a book, and I had to figure out most of it through hard experience. This ranges from document formatting to crafting a good cover to writing a good blurb to figuring out your vendors to—

And don’t even get me started on the business knowhow, the platform-building-savvy, you need to teach yourself to actually get eyes on your book. (Stuff that is remarkably relevant to even traditionally published authors since even publishers don’t know how to get your book out there and into its right audience, but more on that later.)

This is all made even harder by the fact that, to my knowledge, mentors are few and far between for authors and most of the ones that do exist can’t actually help you find success—they can teach you how they write a book, how they find and keep an audience, but there are astonishingly few universal rules to pass along.3

Traditional publishing is racist, sexist, and other forms of bigoted. Yes, it is possible to be racist against whites, it is possible to be sexist against men, and it is possible to be bigoted against straights, conservatives, and christians. Back when I was searching for an agent, it sickened me the number of agents who were very explicit that they were not interested in working with any number of the above traits that I mentioned. Let me clarify myself: they weren’t interested in working with the author who was white, male, attracted to women, etc, despite none of those traits being relevant to the manuscript.

Many other agents were more subtle, but the message was still there: if an agent is only seeking for “queer romance” derived from “true experience,” I know she/they/it/apache helicopter has no interest in a straight author sending a manuscript over.4

In short, it didn’t take me long to discover that identity, by and large, mattered more than merit, at least among the literary agents that I was able to find. I had, essentially, finally seen the near-impenetrable gate between me and my dream.

In the tradpub sphere, at least.

Being a professional author is not just writing, and it never has been. If you want to write and only write, you’re a hobbyist, and the odds of you breaking out are next to zero—and if you do break out, the odds of you maintaining any sort of audience are even lower.

I should note there’s nothing wrong with being a hobbyist, at least for people who solely want to write and that’s their end goal. But more is required if you want to achieve any sort of stability and self-sustainability.

To be a professional author, you need to be willing to (bare-minimum) be a part-time businessman or salesman.

I was first exposed to this truth by Brandon Sanderson—I took his lecture class at Brigham Young University, as well as the smaller class you have to audition for. He started making a living full-time as an author earlier than most (relative to his number of published books), but that still came after years and years of writing entire novels, going to conferences, pitching himself getting shot down, and working less-than-glamorous jobs. But that “great before” isn’t what I’m referring to when I say an author has to be at least a part-time salesman or businessman. No, even after Sanderson got his big break (which could be defined as either getting a deal for Elantris or being chosen to finish Robert Jordan’s Wheel of Time), he still wasn’t getting as much support from his publisher as a green author (or aspiring author) would hope. When his publisher wouldn’t schedule tours or other publicity events, Sanderson figured out how to do it himself. When his publisher decided that specialty editions were too risky, Sanderson bought back the rights and did it himself. Sanderson made a small publishing house built entirely on his own body of works and, even before then, was willing to hire, out of his own pocket, a secretary to assist him with the business side of authorshhip. From the very beginning he sought out his audience and did what he could to maintain that audience while building, and shoring up, a platform. Even now, as probably the biggest name in fantasy alive today, Sanderson doesn’t just write—he formally sets aside a minimum of one full day per week to solely focus on the business end of being an author… But, as he admitted in his classes several times, he still normally has to spend at least an hour or so every day to manage his business and be good to his fans. And, of course, this is to say nothing of time spent on conventions, other events, and travel to and from such things where he may spend a week or more unable to do any meaningful writing.

Don’t forget, Brandon Sanderson is traditionally published. He later chose to transition to a hybrid of traditional publishing and self-publishing (through a self-owned small publishing house), but he began fully traditionally. He arrived in the twilight of traditional publishing’s era; if he had relied primarily on his publisher for all things business and marketing, I don’t think most anyone would know his name today. Say what you will about himself or his books—the criticism he receives, fair and unfair, is a deluge—but what he does works.

No one really does the business side of writing quite like Sanderson, but he’s still far from the only guy who has to work hard on the business side of writing to reach his levels of success—and some do that while still supplementing writing income with… a real job.

Here’s a fun fact I learned from Kristin’s article: Hemingway worked as a journalist to pay his bills. That’s right, one of the most famous American authors to ever exist, and he still had to hustle—not just on his job, of course, but also with leveraging his connections within the publishing industry to get his stories in the right place at the right time. Because locking yourself in a room and only writing has never been a path to author success, even when traditionally published—even when agents and editors, debatably, were worth the cut they took out of your book’s sales.

(Not-so-fun fact: if you don’t have a pre-existing audience or marketing plan, or a really good network, or a famous name, many agents and editors won’t touch you. Yes, it’s gotten rough out there.)

Traditional publishing has no idea how to make names and sell books. This is a widespread problem. The biggest publishers are struggling to get new books from new voices in people’s hands and they are unwilling to innovate. Instead, they publish authors while hoping for an instant mega-hit, then move on just as instantly when that doesn’t happen. Nurturing budding talent? That might have happened once upon a time, but these days no one gets to be a rookie—you start out as star quarterback or you’re off the team.

And, of course, where possible big publishers lean on pre-existing big names to the exclusion of all else, completely stifling their chances of creating new big names.5

This doesn’t get much better as you go down the line. I’m not a superstar researcher, but I couldn’t find any mid-sized (or smaller) publishers that had figured out how to market books and get people excited about them. I found a few indie publishers that had audiences that appeared fairly loyal to the publisher; they’d take on a new author, sell some books to a pre-existing audience, and that would be the end of it—I’m unaware of those authors doing anything more, or going any further, with their work. I couldn’t find any evidence of any authors making a living this way, at least.

Baen used to be the go-to (medium) publisher in this area, having once been the most innovative of publishers, but even they have fallen from grace; and Baen’s spiritual successor, Ark Press, is currently relying primarily on known names like Larry Correia to get their books sold, which doesn’t give me much hope. As well, their “innovations” in publishing include things like Kickstarter, which people have been using for over a decade as one method of book publication. I suppose this counts as innovation when compared to the large publishers, but it’s not actually anything new.

I’ll cut Ark Press some slack: they are extremely new as a publisher. Perhaps they will prove they can take new names and nurture those authors into having real careers. Maybe they will prove that the low royalties publishers pay authors can be justified with real, value-driven guarantees, including (but not limited to) efficacious stewardship over the business and marketing aspect of writing. But I’m not holding my breath.

Note that my pessimism does not stem from Ark Press specifically, nor the guys who built the company, but from the fact that the publishing industry has consistently proven unable (or unwilling) to modernize as well as, or remain as relevant as, other entertainment industries, despite many previous indie presses attempting exactly that. Maybe the mere existence of publishing houses is archaic.6

Break-outs don’t happen anymore. Not in books and publishing, anyway, and not to the scale that they once did (becoming national or international names). You can try to prove me wrong—put examples down in the comments—but no one in traditional publishing is building a career today, or within the past decade, that’s more than a flash in the pan, and the existing crop of established career authors all come from the middle or tail-end of the era of traditional publishing’s dominance.

Now, granted, big break-outs aren’t necessary to make a living off of writing—some mid-listers accomplish it, to my knowledge—but traditional publishing isn’t interested in mid-listers anymore. There’s no publisher or editor who will put forth the time to nurture a budding career that might take off down the line. If you aren’t an instant success, you’re a has-been. But I’ve touched on that already.

I think you can easily see how all of of the above, for me, came together into a pretty clear message: if I want to make a living as an author, traditional publishing is not the way to go. I need to take charge of my own destiny.

Taking Charge

But then the other issue I, and so many others, have run into is this: how does one indie publish?

Well, a lot of new indie authors have naive ideas about how indie publishing works—most often, that they can just throw a book on the market and it will, without effort, start attracting attention. Some of them put in the time and effort to learn how to actually excel in the indie environment; others refuse to put in the work, refuse to learn the environment, very predictably fail, and then blame everything but themselves.

This is where the inspiration Kristin’s article gave me comes in. These paragraphs, right at the beginning, hit me like a truck:

His final post before deleting was a full-on manifesto of why he was done with it all: the audience is fickle, the algorithms are rigged, AI is flooding the market, everyone wants everything for free, and the “business” of writing is beneath the dignity of someone who just wants to write well.

I read it twice. The first time with sympathy, because indie publishing is brutal and I’d be lying if I said I hadn’t felt every one of those frustrations myself. The second time was with a sick sort of familiarity. Because buried in that rant was a belief I’ve seen sink more writers than any algorithm ever could: the idea that good writing should be enough. That talent will find its audience. That if you build it, they will come.

It won’t, it won’t, and they won’t. And pretending otherwise will destroy your mental health and self image.

Talent won’t find its audience. Not by default, at least. And that’s a really hard lesson to learn—because I think almost everyone hopes, or assumes, that on some level they will get some “deserved” recognition just for working hard and making something good. And that can make it aggravating when you see someone who does something objectively worse than you find more success than you. After all, the amount of work you put into something isn’t an objective marker of its value—but most people act like it is. No, value is actually determined by how aware of it people are and how much they want it, whatever it is.

Assuming that talent will bring success by default is a sort of laziness. It’s a refusal to realize that the real world demands a lot more effort than that; and not just more effort, but effort intelligently and effectively invested into areas beyond whatever your passion, art, or profession might be. In publishing, that area appears to be, by and large, platform building, audience building, and marketing.

Here’s an anecdote. My dad loves smokers—as in, he loves to cook meat by smoking it. He raises and slaughters cows, so he’s got a lot of meat to cook. He switched smokers a few months back and I noticed immediately because his cooking, while already good, got better. I asked him what had happened and he told me that he’d realized his first smoker was built by “an advertising company that also made smokers,” but the new one came from a smoker company that also advertised its goods.

It took him longer to discover the second smoker than the first, but he never would have in the first place if the company hadn’t put itself out there at all. And now, should I ever be interested in a smoker, I’ll ask him the name of the second and skip right to it.

I can’t give you any of the answers on how you will find your success, but if you take direct responsibility for your work—in whatever your venture is—your odds of success are going to go way up. Success is never guaranteed, of course, but at least you’ll give yourself whatever counts as a fighting chance. You’ll make mistakes, you’ll have to change plans, you might even think everything has been blown to hell at some point (and it might be your fault), and so forth, but at least you won’t be standing still on a down escalator.

For me, one of my biggest mistakes as an author was publishing book one of a trilogy when I was experimenting with my style and, from the beginning, had intended to publish several other books before returning to that trilogy. Why is that a mistake? Well, two big reasons. For one, a lot of readers nowadays are interested in finished series, which makes standalones a bit of a safer investment. For another, an even larger group of readers get annoyed when an author starts a series and then works on other projects for a while rather than powering through to the end. This decision probably lost me audience that I didn’t even have yet.

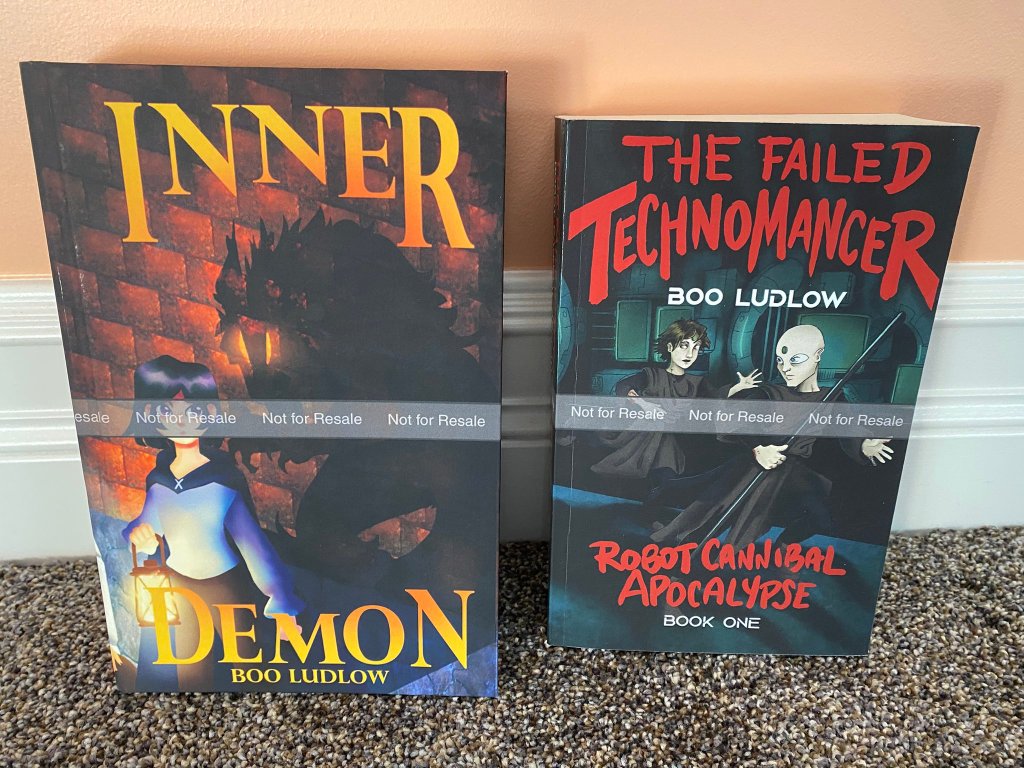

Here’s another thing I’ve done, which may pan out to be a mistake, may not. I learned early on that most indie authors make most of their money off of their back catalogue. To me, that sounded like a strong argument to not worry too much about learning to advertise or build a platform until after I had a few books published. (Halfwhisker is the book I intend to finish and then, after or as part of publishing, start to really focus on learning the business aspect of authorship.) Was that a good idea? Well, it allowed me to spend some time writing that I might have otherwise spent trying to learn marketing, advertising, and so forth. It also meant that The Failed Technomancer and Inner Demon were released to essentially no fanfare or recognition, which will probably significantly hurt their visibility with various vendors over time. That also probably hurt my ability to build an audience with these books and, since these books and Halfwhisker are pretty different books set in different worlds, there’s even less of a guarantee that the existence of a back catalogue will turn into reader pull-through. I’ll just have to wait and see.

I decided to have WordPress be my author website because I didn’t really know anything else. It wasn’t until I was a year or two invested in this site that I learned that most authors are finding audiences on Substack, not on an antiquated blogging site. I’ve been mulling over the risks and rewards of switching over for some time, or the time cost of trying to manage both at once.

A lot of authors build audiences on social media platforms like X, Facebook, Instagram, and TikTok. Frankly, I hate all social media, but I hate X the least, so I’m giving it a try. I imagine eventually I’ll have to learn to be a much more engaging personality on one of those sites to try and drive as much organic reader engagement as possible—I don’t believe that social media is the end-all be-all of authorship, of course, but I want to at least try to best utilize my resources.

I’ve also learned that long blog posts and long books tend to have smaller potential audiences, yet I keep writing them. That’s probably something I’m just going to define as uniquely me, since I have no interest in writing shortly just for the sake of shortness. Whether or not that’s a good hill to die on, time will tell.

I’ve got a lot to learn, and I’m sure there will be a whole lot of mistakes to make along the way—but there’s hope.

Inspiration

There are a lot of indie authors out there who are making it, at least in the ways that I’m interested in making it—that is to say, they are making a living off of writing.

But, interestingly enough, those aren’t the authors that inspire me the most. Maybe that’s because a lot of career authors initially found their successes in a yesteryear; yes, they need to adapt to the times to at least maintain their audience and income now, but they aren’t growing alongside me. I find a lot more inspiration in authors who are closer to the same boat I’m in.

Devon Eriksen goes at the top of this list for me. If you read indie I’ll be extremely surprised if you haven’t heard of him—Theft of Fire is a stellar read (pun fully intended) and appears to have unusually strong reach for an indie novel, particularly for an indie novel that’s the author’s only published book to-date.

When I first read Theft of Fire, I wished I could write that well. But instead of getting down on myself, the book inspired me to try harder and do better. And Devon himself does that with his frequent long posts on X where he discusses anything, ranging from his libertarian politics to how he thinks indie publishing ought to be done, ideally—and maybe it’s because he’s actually struggling through at the same time that I am (albeit he makes the struggle look a lot easier), but I find his advice a lot more useful and applicable than that from authors who have been writing for a living for ten years.

Next up is Gregory Michael. For whatever reason, my review on Chloe’s Kingdom is one of my most-read reviews on my blog—but the book deserves the attention, so I hope that means I’ve been able to help Greg find more readers. Anyway, I discovered Greg back when he stood up for Devon when an indie sci-fi contest attempted to cancel Devon; Greg received a bunch of well-deserved attention from his good act.

Greg’s hustle is better and more focused than mine is, and he’s got a much more defined brand than I do, but so far as I’m aware we both got serious about indie authorship within about a year of each other, we both have the same general goal of making a living writing, and, at the moment, we both have two books published. We are not the same, but we have enough parallels that it’s a lot easier to feel like I’m in the same boat with him than I feel when I compare myself to other authors.7 Cheering him on for his successes, seeing random posts where people praise Chloe’s Kingdom—it feels good, man. It gives me faith that there’s a rising tide in the indie sphere and that my boat will be raised with it.

Last for the purpose of this blog post, but certainly not least, is Michael F Kane.

I. Love. After Moses. I like big books. I like multiple viewpoints. I like long series. I like epic scopes. In every single way Kane’s books scratch all the itches I want scratched—with the exception that he writes science fiction instead of fantasy, but that’s forgivable when he’s stellar in so many other areas. (Pun still intended.) His wholesomeness as a person, how well he weaves uplifting messages into his stories without ever getting preachy, actively inspires me to become better and to do better with what platform I have. He’s been an indie author a lot longer than me—and I also think he’s just plain better at writing than I am—but he sets a high bar that I’m absolutely going to keep trying to reach.

To my knowledge, none of these authors are making a living off of their writing—yet. But I believe in each of them. And watching them, and trying to make something for myself, really motivates me to keep pushing forward.

I also can’t help but notice that every one of these authors are sci-fi. Fantasy is sorely lacking in the indie scene, at least as far as books that catch my interest are concerned—which cuts out most of the fantasy books I’ve found, which appear to be treating indie authorship as an opportunity to get even more explicit than traditional publishers would allow. Ick.

Where I’m At

To finish up, I want to quote Kristin’s article one more time.

The writer who quit was talented. I meant that. But talent has never been enough, and it’s never going to be enough. The world is full of talented writers who never build an audience, never make money, and eventually give up in frustration. What separates them from the ones who succeed isn’t some mystical quality or unfair advantage. It’s willingness to learn the parts of the job that aren’t writing.

You can hate that this is true. You can think it shouldn’t be true. You can argue that the system is broken and writers deserve better. I reckon you’re right. But while you’re waiting for the system to change, other writers are learning to navigate it, and they’re building careers.

If you’re not willing to learn the needed skills, that’s your choice. But don’t convince yourself the choice is being made for you. You’re choosing to stay helpless.

Transforming from a writer to an author—a professional author, anyway—is hard. And being partway through the metamorphosis process is pretty ugly, as you’re left half-formed in most areas, some areas haven’t started changing yet, and the areas that have reached their final form might not yet have a discernible use until the rest of you catches up. Be patient.

I’m trying to be. It’s not easy. But I trust it will be worth it, with time.

I choose to take charge.

Enjoy this? Please consider subscribing! I post new blog posts most weeks—usually these are reviews, but I’m playing Silksong right now and am at fifty or so hours deep with no end in sight, so it’s taking longer than usual for me to work through things and share them.

Another way to support me is to check out my books! You can read The Failed Technomancer for free, in its entirety, right here, or you can buy it here. Try it and you’ll find some fun, dark science fantasy, as well as people-eating robots. Alternatively, if you prefer just fantasy, Inner Demon released recently, and I’ve even managed to get the audiobook live on a variety of sites so far. You can buy that using this link.

- Some would also include people who had a book ghost-written within the “author” umbrella—these people are insane and do not deserve serious consideration. ↩︎

- Yes, this is a skill that can be learned—the agent querying. You don’t have to remain blindfolded. ↩︎

- Here are two: have an author website and get a mailing list. I’ve got one. I’ve kinda started on the other. I haven’t “figured out” either. ↩︎

- I’ll be honest, I rarely sent manuscripts to these authors because I knew it was a lost cause, but every once in a while something would give me hope… that never panned out. ↩︎

- I’m not going to blame a publisher for continuing to publish work from a proven author—especially one they “found.” Any publisher that gets the chance to publish an Abercrombie novel, just to pick a name off the top of my head, is probably foolish to turn it down. But prioritizing name brand of celebrities and others who aren’t really authors over buddy, actually-and-author talent tends to produce poor books and reduce reader trust in traditional publishing. That’s the bigger issue I see here. ↩︎

- Big companies and entrenched powers in other industries, such as video games and movies, are struggling right now, too. Dare I hope that the age of smaller studios and creative powers is upon us? Well, more blatantly, since a lot of the best art being produced right now is already coming from the indie sphere.

Ugh, I sound like a hipster. And that reference probably makes me sound dated. My daughters are going to gag if they ever read their dad’s author blog. ↩︎ - Don’t compare yourself to other authors. Most of the time it will just bum you out. (If you’re careful, you can learn from the successes of others without having to make unhealthy comparisons, though.) ↩︎

Leave a comment