That’s a mouthful of a title.

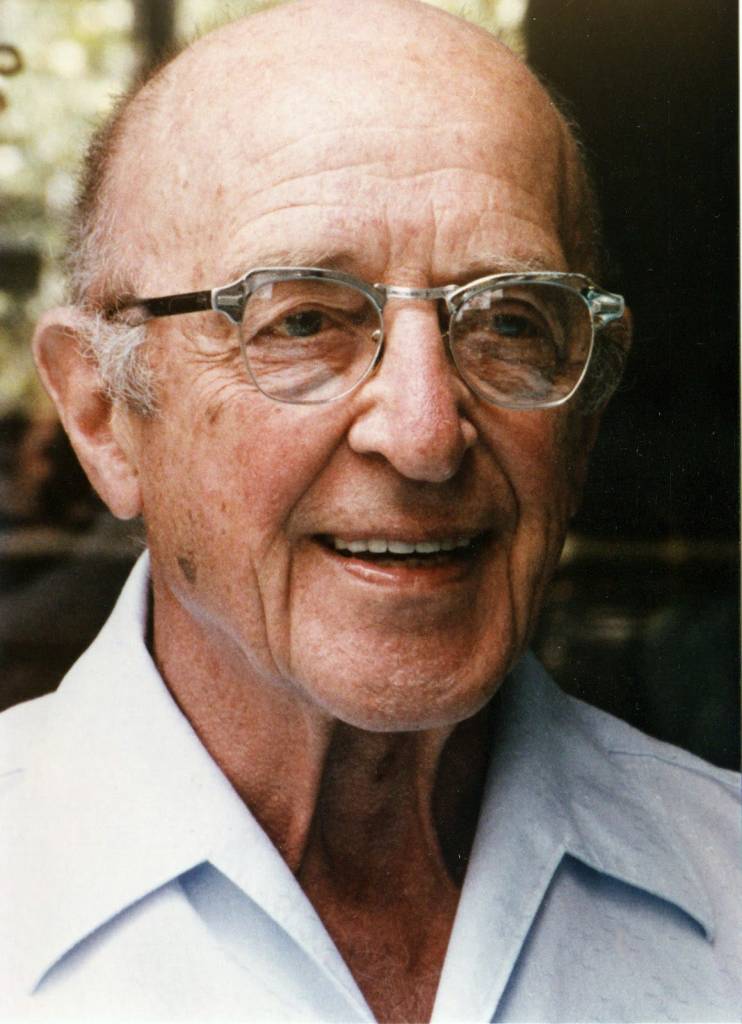

Here’s how we got to this unusually-timed, unusually topic’d blog post: my friend, Tanner, has a Substack called Crafting the Good.1 (I’ve entered into dialogue with him, through these posts, once or twice before.) After reading his most recent article, The Semantics of “Reality” w/ Carl Rogers, I was unusually strongly compelled to respond. I largely agreed with what Tanner was saying—but, especially after reading Do We Need ‘A’ Reality (Carl Rogers; the essay Tanner was responding to), I thought Tanner was being far too charitable in his interpretation of Rogers’ essay. Mr. Rogers deserved to be slam-dunked into a basketball hoop with his flaccid takes.

I’m going to start this blog post/article off with some direct responses to Mr. Carl Rogers, then comment a bit on Tanner’s article (not as much, since I think I agree with Tanner in most areas), and finish off with a miniature dissertation on my own thoughts on what reality is and why that matters.

(If you want to skip directly to my thoughts on the nature of reality—I’ll begin with enough of a summary that you’ll be able to follow along even if you don’t read what came before—just click here.)

But why, you might say, all this rather than another review, newsletter, or update on my own writing journey? Well, Tanner said it best:

Sometimes I hold off from writing about a topic because it isn’t directly related to the art and craft of writing. But then I remember that writing is a mimetic activity—we are trying to mimic, express, capture, twist some version of reality.

And the truly powerful authors, the ones who teach us, are the ones who are able to capture aspects of reality that go ignored or unexamined.

Tanner Millett

Do We Need ‘A’ Reality (YES)

I had a very hard time finding a copy of Mr. Rogers essay and ultimately had to be gifted a PDF copy—as such, I’m going to try and have my quotations from Mr. Rogers’ essay be on the large side to try and provide as much context as possible, as I imagine finding the original source will be difficult for most people.

That said—for all those who have not read Do We Need ‘A’ Reality, I think I can fairly summarize the ultimate point Mr. Rogers is trying to make using his own words:

Where have my thoughts led me in relation to an objective world of reality?

It clearly does not exist in the objects we can see and feel and hold.

It does not exist in the technology we admire so greatly.

It is not found in the solid earth or the twinkling stars.

It does not lie in a solid knowledge of those around us.

It is not found in the organizations or customs or rituals of any one culture.

It is not even in our own known personal worlds.

It must take into account mysterious and currently unfathomable ”separate realities,” incredibly different from an objective world.

I, and many others, have come to a new realization. It is this: The only reality I can possibly know is the world as I perceive and experience it at this moment. The only reality you can possibly know is the world as you perceive and experience it at this moment. And the only certainty is that those perceived realities are different. There are as many “real worlds” as there are people!

Yes, relative to the length of the original essay, that chonker of a quote is a summary. But let me sum it up even further in my own words: Reality is subjective. I’m not sure there’s any other way to interpret the claim that There are as many “real worlds” as there are people!, particularly when Mr. Rogers is trying to succinctly state his thoughts on “an objective world of reality”.

To attempt to steelman Mr. Rogers, I’m skeptical that he truly believes reality is fully subjective in every sense, whether or not he realizes that. He points out near the beginning of his essay that we’ve proven that the earth rotates around the sun, that we are not the center of the universe, even in awe-inspiring moments where it might feel like we are; that physical objects have a lot more empty space within them than one might guess from pure observation, being made up of atoms which are, by and large, empty space; and, as an example beyond the purely physical realm, that we can know our friends and family fairly well on a personal, emotional, and intellectual level, even if it’s not possible to literally know every thought or feeling a loved one possesses.

In other words, we are all imperfect human beings who have an imperfect knowledge and reception of the real world around us, of things both physical and mental, emotional, or spiritual. Or, in other words, everyone has a different perspective of absolute reality and all its facets. That’s a fair and obvious statement.

In fact, replacing “reality” with “perspective” is how, in his own essay, Tanner finds common ground with Mr. Rogers. By my reading, there’s a weakness here, and that weakness is that Mr. Rogers can’t seem to settle on what reality really means!

Yes, at times “reality” could mean “perspective,” as he uses the word. At the start of his essay, Mr. Rogers compares his personal experience of feeling as if he were standing still against the literal reality of the fact that the planet he was on was turning rapidly and was flying through space rapidly. In this instance, perceived reality and literal reality are very different; there’s a reason we as humans usually operate within a shared perceived reality that exists relative to a shared state of being—imagine if our car odometers had to take into account the movement of the planet and add that to how fast you’re driving on the highway. Such a thing would obviously be insane and impractical.

Here’s another type of reality present in Mr. Rogers’ essay. He points out that you don’t know the secret thoughts of friends and family; there might be “bizarre sexual desires and fantasies” hidden from you, or other things, so therefore you don’t really know them, and therefore you don’t really know “reality.” Well, this isn’t an issue of physical reality or perceived reality, but more a lack of knowledge. Of course nobody knows the entirety of somebody else’s head—nobody does!

And then Mr. Rogers gets weird with it—behaviorists say that conscious thought is an illusion created by inputs received and conditioned outputs. In short, you aren’t you, but you are a meat computer. (“Or is that all?” Rogers counters. “Where do my dreams come from?”) Well, now we’re looking at philosophical definitions of realities, not physical realities, perceived realities, or levels of knowledge about aspects of reality.2

Once upon a time a woman named Jean felt the exact moment her twin sister died in a car crash. That exists in reality; in my opinion, stories like this, if true, can only be explained as an expression of spiritual reality—scientific explanations of such events fail to be replicable, after all—which is yet another type of reality that Rogers casually refers to with the same word. (He has a few other examples, as well, that I think most reasonably refer to spiritual reality.) Then there’s the scientist John Lilly, who used sensory deprivation tanks and, not at the same time, LSD to reach, as Rogers describes it, a “higher state of consciousness”—this sort of “reality” is purely internal reality, even more so than just perceived reality, as Lilly very intentionally altered the functions of his brain chemistry for a time—which, if I’m not being clear, does not change reality itself, solely his perception of reality—and of course that’s going to result in him experiencing the world differently!

And that’s all aside from the fact that calling a drug-induced state “higher consciousness” is pretty suspect at best—if such a thing were true, I met a lot of drug-addled hobos in Jamaica whose mutterings I ought to have written down. Their thoughts and insights on the world must have been mind-shattering, truly beyond my comprehension, because I just interpreted them as pitiable gibberish.

If Mr. Rogers were more consistent, or if he directly provided a definition of reality anywhere in his essay, then the essay might not have any inconsistencies, or such inconsistencies might fade away in context, but that’s not the case. As presented, if reality means everything, essentially, then him stating that reality doesn’t lie in anything, that it only exists for me as I perceive it in this moment and for you as you perceive it in this moment—not even taking into account historical experiences—well, can you understand how I think the only possible conclusion is that Mr. Rogers sees reality (and therefore truth) as completely relative?

Well, no, not quite—whether or not reality is absolute or relative, Mr. Rogers’ argument is really that our perception of it is unalterably relative—which means that, for all practical purposes, reality is relative, because humans are only capable of interacting with it as if it were relative.

What rubbish.

Mr. Rogers disproves this idea in his own essay—he points out that multiple scientists across the world independently discovered (or developed) quantum mechanics at about the same time. If everyone existed in their own reality, this would be impossible—the fact that they all came to the same conclusions suggests that they must have been measuring something objective, something universal across time, location, and personal experience or perspective—and they all were able to experience these shades of absolute truth cutting through their own perceived realities! There’s no room for “individual realities” in this bit of “evidence.”3

And while I’m tearing this essay apart, I haven’t yet mentioned some some astonishingly bad takes. Like Rogers’ thoughts on Hitler:4

Today we face a different situation. The ease and rapidity of worldwide communication means that every one of us is aware of a dozen “realities”; even though we may think some of them absurd (like reincarnation) or dangerous (like communism), we cannot help but be aware of them. No longer can we exist in a secure cocoon, knowing that we all see the world in the same way.

Because of this change, I want to raise a very serious question: Can we today afford the luxury of having “a” reality? Can we still preserve the belief that there is a “real world” upon whose definition we all agree? I am convinced that this is a luxury we cannot afford, a myth we dare not maintain. Only once in recent history has this been fully and successfully achieved. Millions of people were in complete agreement as to the nature of social and cultural reality—an agreement brought about by the mesmerizing influence of Hitler. This agreement about reality nearly marked the destruction of Western culture. I do not see it as something to be emulated.

Upon reading these paragraphs, I was utterly flummoxed at the sheer, mind-bending stupidity of these printed words. I had to read it again. So, according to Mr. Rogers, I can only know my reality and you can only know your reality; yet, somehow, some way, the sole modern instance of not just a handful of individuals, but millions of individuals, overcoming this seemingly insurmountable barrier to having a fully shared reality… was when Hitler swept through Germany with the rise of Nazism?

Is that not utterly insane?

This statement becomes less insane if you interpret “reality” in this specific instance as “cultural reality,” “social reality,” or “philosophical reality”; in other words, if Rogers were discussing the danger of a man like Hitler persuading a nation of people to share with him beliefs about reality that don’t just justify genocide, but necessitate it, and if Rogers were pointing out that such reality-altering beliefs were bad—well, no duh. That’s one of the most room temperature takes I’ve ever heard.

But that point, as it exists in the essay, is still utterly broken no matter which direction you take it. If Rogers really was talking about belief systems—he starts by suggesting that shared belief systems are a “luxury” that are very dangerous. If that’s the case, he’s casually equating all belief systems—from Christianity to Islam to Capitalism to Stoicism, and more—with Nazism. Which is so insane that as I type this I’m screaming at myself, “That’s not what Rogers meant!”

Well, fine—but then what did he mean, if Mr. Rogers were speaking not of all realities as one, but of social, cultural, or philosophical reality? Simply that there exist extreme ideologies that give individuals dangerous perspectives of reality? That’s it? Such a statement is true and not not worth saying—but Rogers hardly brings anything new to the table if this is his goal.

What if Rogers were genuinely treating all realities as one, as his use of the word “reality” implies throughout his essay? What if he were truly implying that the only time in modern history that all forms of reality were united was under Hitler and Nazism? Comparable world villains known for abominable genocides and other atrocities, like Mao and Stalin, were not able to unite their peoples in such a way under their visions of evil. No good or altruistic religion or secular ideology ever united in such a manner in the modern era (apparently). Solely Hitler and Nazism has created a shared reality—among millions, anyway.

If that’s true, then Hitler was some sort of reality-redefining wizard—or maybe he was right. Which, I must be clear, is not the point Rogers is making (nor I)—it can’t be. But whatever point he was really trying to say, he said it extremely sloppily and muddily.

There’s more I could say, but I’ve kicked this dead horse enough times—suffice to say, Mr. Rogers likes playing with his idea of everyone being an island, but he can’t support the idea at all and hasn’t seem to have fully thought through his claims.

Let’s move on.

The Semantics of “Reality” w/ Carl Rogers

Since Tanner’s article is mostly a reframing of Mr. Rogers’ essay—I think that’s the best way to put it—I don’t want to spend too much time on Tanner’s direct arguments. After all, I largely agree with Tanner’s charitable reinterpretations and, where I disagree with Tanner, I don’t think he deserves the skewering that I gave Mr. Rogers.

Tanner’s most important correction of Rogers is that he actually provides a definition for absolute reality: for Tanner, that absolute reality is “Truth, and Truth [is defined as] all that has been, all that currently is, and all that will be… and the relationship between these things.” This absolute reality includes all of Rogers realities within it; meaning, an absolute state of things as they are and were and will be exists (whether physical, mental, spiritual, etc), but that reality is able to include our perception of this absolute state, as well as the perception of others. That’s not to say that perceived reality overrides absolute reality, of course, but that it exists as a reflection of reality (if, perhaps, one seen through a funhouse mirror).

What the heck, I’ll share the quote about how perceived realities fit into this definition; Tanner probably said it better than I did, and certainly more succinctly:

Reality contains a full awareness of positional relativity and the human psyche.

So, yes, whether you agree with it or not, Tanner’s definition is extremely workable and provides an excellent starting-off point for the rest of what he has to say.

Anyway, Tanner builds on all this by pointing out that our relationship with reality is not a binary. Yes, it’s most likely impossible for our mortal, flawed selves to be able to fully grasp absolute reality in this life, but we are able to grasp pieces of it. We are able to handle degrees of it and, if we want to, our continual search for more truth and reality can bring us closer to the absolute over the course of our lives.

Within this reframing, Rogers’ closing utopian idea that we should accept “new realities” and constantly seek other “other realities” is given a more meaningful purpose than just making ourselves feel better and magically making the world a better place: since I have knowledge and truth that you don’t have, and visa versa, it becomes my responsibility to teach others and learn from others so we all can come closer to absolute reality together, and you share in this responsibility. (Tanner doesn’t explicitly state this, but I think Tanner implies that this all comes with a responsibility for me to cling to the truth I do have, to whatever degree it may exist, and never accept a lesser truth, or especially an outright illusion, in its place; and, of course, not just me, the reader of his article, but all seekers of truth.)

And, of course, paired with this knowledge—to whatever degree of absolute truth it contains—is the responsibility to act according to that knowledge.

Humility is recognizing we cannot know full reality in this life. It is the courage to act even when we’re aware that our knowledge is yet incomplete.

In short—Tanner, I think your reframing of Mr. Rogers’ essay was insightful, but I state that you’re reframing Mr. Rogers’ essay perhaps too charitably because he doesn’t actually state your enlightened interpretations of his words.

Which, perhaps you already agree with and I’m being a pedantic ass. If so, I’ll blame being on the very edge of the spectrum rather than taking responsibility for myself. *wicked cackling ensues*

Before I move on to my direct thoughts, I wanted to share one more quote from Tanner, this one because it made me chuckle.

We… cannot comprehend that full reality.

But that doesn’t mean it isn’t there. We cannot assume full and comprehensible reality does not exist simply because we cannot see it. Such an assumption would make us little wiser than infants who have no sense of object permanence.

Do you remember the “blanket disappearing challenge”? When people would hold a blanket up, shake it, then hide or otherwise “disappear” when the blanket fell? I’ll include a video example below. Here’s the connection: assuming that an absolute reality does not exist, or that it’s not comprehensible on at least some level, makes us the children in the below video and “reality” the disappearing dad. That’s the connection my brain made to Tanner comparing such people to infants with no object permanence.

Reality™, by Boo Ludlow

Let’s see if we can bring this all together, and then build on it.

— Absolute Truth, Absolute Reality, Summated —

Absolute reality, and therefore absolute truth, exists. Tanner’s definition is a good one, so I’m going to run with it mostly as he stated it: absolute reality is “Truth, and Truth [is a knowledge of] all that has been, all that currently is, and all that will be… and the relationship between these things.”5

Why does this assertion matter? Its matters because reality and truth either exist in absolute forms or they don’t—and if they do, then we must seek the best knowledge of these things that we can find and act according to that knowledge and truth. After all, living in accordance to truth ultimately brings peace, happiness, and all other good things; acting against truth ultimately brings pain and suffering. (I say ultimately because doing what is right [acting in accordance to truth] sometimes comes with initial pain or hardship, while doing what is wrong [acting contrary to truth] sometimes comes with initial pleasure of some sort.)

I should clarify that absolute reality and absolute truth (at least defined as a knowledge of all things that have been, that currently are, and that will be, and the relationship between these things) does not solely refer to physical reality. Various moral ideals exist, being self-evident; they are things that are (and were, and will be), despite being untouchable and not directly observable as literal objects or images. As another example, history was, and its effects are felt now and will be felt, even though it is impossible to reverse time and directly interact with history. I will refer to these smaller portions of the whole of absolute reality as spheres going forward because they encircle many things, things which, again, are, were, and will be, and create relationships within themselves and with other spheres. There are too many non-physical spheres for me to list here in their entirety: mental spheres, emotional spheres, spiritual spheres, and so forth.

And if I wasn’t being clear enough earlier, physical reality is its own sphere, related to all of the others, influenced by and influencing them, none of them islands unto themselves, but all easier to initially conceptualize when categorized according to these sorts of themes. An elephant is best eaten one bite at a time, after all.6

So, if absolute truth is, then it must also be observable, measurable, and testable—and, therefore, knowable. (There’s where my addition to Tanner’s definition comes in.) In other words, anyone, given the proper resources and mindset, can discover the same absolute reality as anyone else, thereby piercing through perceived realities, and can do so fully independently if so desired. (I don’t recommend total independence, as so much is already known and doesn’t need to be rediscovered the hard way, but anyone who wants to can confirm that, as an example, honesty objectively exists and improves the life of the honest and the world around the honest. Some people just have to learn lessons the hard way, I guess.)

Finally, if absolute reality and absolute truth is; if it is observable, measurable, and testable; and if absolute reality is therefore knowable; then absolute truth is practically applicable as well.

Or, absolute truth and reality do not exist in logic or theory, but in action.

— Actionable Reality —

Reality is actionable—in other words, it can be directly interacted with or it can be put into practice. The material world can often be observed and tested in a lab; the immaterial world, often but not exclusively, is experienced. In either case, this is where testability and then knowability comes into practice.

I’m going to start with physical reality to provide some easy examples. Imagine a solid brick wall with a firm foundation standing in the middle of a field. Anyone can learn the absolute reality of the existence of that wall by seeing it and interacting with it. Anyone who, through insanity or the most stubborn of disbelief, refuses to acknowledge the reality of the wall will quickly be set to rights upon attempting to run through the wall—the wall will win over human flesh and bone, suffice to say.

And that wall stands just as well, functions just as well, and blocks light and human skulls just as well for the man who is completely insane, the man who knows nothing of modern science, and the man who makes it his profession to research the subatomic particles of the elements that ultimately constitute that wall’s bricks.

Physical reality is pretty easy to observe and test (generally and relatively speaking). The modern, Western empirical approach has proven incredibly effective at doing exactly that, allowing us to understand the and manipulate physical reality so as to create marvels and wonders that have dramatically improved human live across the board.

Before I continue, there’s a quick tangent I need to address here: absolute truth is not a binary in the sense that one either has it or doesn’t. Shades and shards of absolute truth exist everywhere. Gaining more knowledge might dissipate previously held illusions, but it doesn’t invalidate previously owned true knowledge; rather, expands on and builds on existing knowledge.

As such, the fact that mankind continues to learn new truths about physical reality that we can’t explain yet doesn’t change the fact that things can still be known to a workable degree and put into practice. For example, no one has managed to definitively prove how gravity works and no one has managed to artificially create gravity in a lab; that doesn’t stop us from having a practical, working understanding of gravity that is universal regardless of personal experiences—and location. We still possess a piece of absolute truth with regards to this portion of physical reality’s sphere.

Increased shades of knowledge make it easier to put into practice the knowledge we have and to accurately predict how applied knowledge will function in practice; the less knowledge possessed, the harder it is to apply what someone “knows,” and the less accurate and consistent that application will be. For example, the fact that gravity doesn’t function off-planet identically to on-planet might make someone who doesn’t have a full enough understanding of gravity conclude that gravity is completely relative. Someone else might assume that all of space has a particular gravity in a particular direction (if such a person is aware of outer space); some real-world cultures have assumed that the force that pulls objects down is caused by spirits rather than natural laws7; etc.

Continuing on, elements of nonphysical spheres of reality are, like elements of the physical sphere, able to be observed, interacted with, and put into practice. It is my experience that many aspects of these spheres of realty cannot be proven or understood until sincerely put into practice in one’s life for a time, while others are most easily observed over the course of generations (in other words, are lessons most easily learned by studying history). It is also my experience that knowledge of these truths comes gradually.

The evidence of the reality of these truths is in their results: “by their fruits shall ye know them.” If you find good “fruits”—if you become a better person, if you find greater fulfillment in life, if you improve the world around you, and all this over time—then you’ve discovered a portion of absolute truth. If you find bad “fruits”—if you become a worse person, if life becomes increasingly miserable, if you make the world around you worse—then you’ve discovered an absence of truth.8

Here are some examples that come to my mind:

- Spiritual: The Existence of God. Sincerely pray to God and live His commandments for a time and the reality of God will be revealed to you. Ignore God and you’re unlikely to ever know one way or another.

- Moral: Chastity. Sexual abstinence before marriage, and total loyalty to one’s spouse within marriage, consistently leads to improved metrics of living across the board. Married, loyal partners typically report higher rates of happiness and better health, are more likely to remain together (and keep their families whole—which leads to far better average outcomes for the children)—and often have more sex, and more regular sex, than the sexually promiscuous, interestingly enough.

- Virtues and Ideals: Power is Violence. All forms of true power are ultimately backed up by violence—if you don’t believe me, don’t pay your taxes, resist subsequent arrest, and then tell me where the government ultimately derives its power from. Even God in the Bible enforces His will through violence, at times using miracles such as floods to destroy the wicked, or allowing violence against His covenant people as a punishment for wrongdoing.9

- Ideologies: Capitalism. Capitalism, when put into practice, lifted more people out of poverty—even people not directly participating in capitalism—than any other economic foundation in the history of the world. Capitalism also produced the circumstances to allow for the greatest scientific and social revolutions bar none in the history of the world, and that within astonishingly short periods of time.

- Social Organization: The Family. Cultures and peoples that put the family at the center of social organization and adopt practices that protect the family tend to be happier, more stable, and more prosperous. Individuals who become the kind of people capable of creating loving, supportive families have a higher standard of living—the highest if they are fortunate enough to form a family, but still higher than they otherwise would have even while still single.10

Please note that I’m not trying to say that I have reached pure, absolute truth with any of the above examples—but I am saying that, through personal experience or observation of peoples and histories, I have learned these things that I believe to be, at the minimum, shades of absolute truth, and I also have learned that all of these shades of absolute truth are applicable in the real world. In other words, you can do or test each one (or study the history of nations and people doing or testing each one) to know for yourself.

— Perceived Reality —

But here’s where things start to get messy. I’ve already rejected Mr. Rogers’ idea that we can only know our own perspectives of reality in the here and now; if absolute reality is testable, then it is knowable, and if it is testable and knowable then it is possible for the dedicated to cut through perceived realities using at least a portion of absolute truth, and even to see inside the perceived realities of others.

But that doesn’t change the fact that not everything we know is true, even things we deeply believe to be true. In addition, we may know things that are true that others don’t know, or might not want to know. (In fact, some people are doggedly determined to cling to their illusions, or—perhaps because of mental health issues, perhaps because of social conditioning—are literally unable to see the light, as it were.) These are facts of reality, of being imperfect mortals with a limited existence living in an imperfect world, like it or not, and such things can make the pursuit of absolute truth muddy at times.

So let’s look at the opposite of absolute truth: things that are absolutely not true, or that may only hold a small sliver of truth and, through the way we apply them, actively move us further from absolute truth.

In other words, absence of truth.

I call these things idiopsychoses. It’s a word I made up. A “psychosis” is a loss of touch with reality; the addition of “idio” refers to an individual. In other words, and idiopsychosis is an illusion (an absence of reality) that someone clings to and believes to be true—or chooses to adhere to despite knowing it isn’t true.

Idiopsychoses are part of our perceived reality. They mix with the absolute truth that we do have, sometimes covering it, sometimes driving it away. Sometimes our most cherished beliefs or personality traits are idiopsychoses. Unchallenged—or insulated from meaningful challenge—they can spread or espand like a cancer.

But the most universal trait of all idiopsychoses is that they always lose to absolute reality when they directly challenge it.

Such a challenge is often painful. Such a challenge may be extremely harmful to the person who challenged reality and was weighed, measured, and found wanting. Some still cling to their idiopsychoses after the fact, even if all evidence tells them they only possess an illusion; in fact, some idiopsychoses self-affirm through failure, and those are particularly pernicious.

This is where the value of sharing perceived realities and striving to understand the viewpoints of others comes in.

Tanner corrects Rogers’ by arguing that seeing other realities should not be an end-goal in itself, and he’s correct. The purpose of seeking out the perceived realities of others should always be in an effort to understand more of absolute reality afterward. Sometimes the lessons someone else has learned can help you overcome one of your idiopsychoses with less pain and suffering; sometimes you can be the balm for another person. Perhaps, after learning of someone else’s perceived reality, you discover they have thing to teach you, or you them; this will happen at times, and you shouldn’t assume that you must learn something from everyone you meet.11

Not everyone has good lessons to teach—and what some people share must be actively rejected or fought against.

Statements like “facts don’t care about your feelings” offend the idiopsychotic because they reveal the foundations of their illusions as exactly that—illusions. Feelings are a part of reality, but they don’t redefine reality—though they do sometimes get in the way of accepting it.

Tolerating, entertaining, or even encouraging idiopsychoses can be horribly destructive, but doing anything else is anathema to those who have thoroughly rejected reality, making people who are fully invested into lies quite dangerous. Unfortunately, a lot of mass psychoses are sold as truth today; as an example, telling men they can be women has already done demonstrable physical and psychological harm to individuals, women, children, social organizations—and yes, men too. And that’s to say nothing of how such lies enable predatory activity. What’s most bizarre is how blatantly obvious this wholesale rejection of reality is, yet many will cling to those lies as if they are their only lifelines. (They aren’t—they are anchors tied to the neck, and we’re all swimming in rough waters.)

Cling to the truths you have. Unless you are given firm reason to believe something you hold to be true is actually an idiopsychosis, do not allow it to be destroyed by another perceived reality simply because aspects of that reality are different or new, popular or vogue; but, at the same time, figure out a balance so that what you hold and incorrectly believe to be true doesn’t ossify or become cancerous, or so that you lose the ability to improve the truth you do possess. Focus on growing and expanding the truths that you already do know, in addition to adding new ones.

And then, in all ways, act according to that truth. When you fail, pick yourself up and try again.

Note that I’m not saying we shouldn’t try to understand other people or build sympathy; quite the opposite. Learning another person’s perspective can help you more easily interact with that person and share what truth you know. But if you are looking to learn of other perceived realities for the purpose of improving communication and understanding, then you already have a constructive purpose for doing so. After all, there is no inherent value in learning other perceived realities just because. Doing so can be fun, but that’s the extent of it.

Never make the mistake of abandoning the genuine truths you have in favor of adopting another idiopsychosis. And don’t assume that other perceived realities are better just because they are different or unfamiliar. Guide all your actions by the truth you know.

Be wise; what more can be said?

— Limited Reality —

I find it unlikely that our mortal, imperfect selves will ever grasp absolute reality in its entirety in our lifetimes—although I wouldn’t complain if that happens. But the search for absolute reality is not a hopeless one, as every collected piece of truth grows one’s personal knowledge and improves one’s life, and allows said one to better influence (or directly improve) the lives of others.

Said the philosopher:

Absolute Truth is to have the humility to acknowledge that we don’t currently know everything. If we are vain or foolish enough to think that current science or current religion explains all that there is to know, then of course we will become confused when we encounter something new! Such a solid worldview does not provide the disposition to see more and more of reality every day, every year.

Humility is recognizing we cannot know full reality in this life. It is the courage to act even when we’re aware that our knowledge is yet incomplete. It is faith in a Creator who has made sense of REALITY, who comprehends all things, and who offers to help us understand it as well if we will follow Him.12

Tanner Millett

This is why seeking absolute reality is always worth it. Doing so doesn’t just bring increased knowledge, but also humility, and confidence. These things can bring courage to strive into the unknown, and to help you see the face of God.

I felt like talking about all of this because I believe that fiction, though by its nature not literal reality, can capture and convey some valuable pieces of absolute truth better than nonfiction can. Also, because entertainment is good and valuable, and I imagine that’s part of absolute reality, too.

In short, I don’t think creators of fiction and entertainment perform the same sort of vital role that farmers and doctors do—Maslow’s Hierarchy—but there still is genuine real value that changes and improves the world, held in story and in its influence on culture. (Degradation of culture can lead to the destruction of said farmers and said doctors, undermining access to basic needs. So who’s the real heroes, huh?13) I’m trying to do my part to shore up what is good and right, even if, most of the time, that comes through reviews of what I’ve read or watched, and only twice now come through a published work of my own.

Other, Unorganized Thoughts

History. Part of the reason it is important to study history is because our ancestors deeply understood truths that we have lost. Our ancestors also held deeply flawed views of reality, but that does not they deserve to be rejected wholesale. Take the good, leave the bad in the past (as much as is possible), but doing so usually requires learning as much as possible of both good and bad.

Empathy. Tanner and Mr. Rogers both discuss empathy. I don’t like empathy. I don’t think it exists. I believe that learning other perspectives builds sympathy. In this way, I share Charlie Kirk’s14 perspective:

I can’t stand the word empathy actually. I think empathy is a made-up, New Age term that — it does a lot of damage, but it is very effective when it comes to politics. Sympathy I prefer more than empathy.

Differences. One of the most destructive, empty feel-good statements Mr. Rogers made is the following:

I prize and treasure you because you are different from me.

The world simply does not work that way. Differences don’t bring people together, but commonalities do. And that’s part of the joy of seeking absolute truth; since absolute truth is absolute (and true) regardless of perspective, people from wildly different walks of life can find commonalities and become united through seeking absolute truth.

Find shared values. Differences, at least when they become the focus, only divide. I don’t think there’s any clearer evidence of that than our modern world—never before has there been so much forced focus on what makes people different, on “diversity,” on highlighting differences over commonalities, on forcing together people with wildly different beliefs and values and then telling one group they aren’t tolerant if they don’t blindly accept the next—and it all has only produced increased division and increased hate. (Unfortunately, the idiots in charge of various institutions most often respond by applying more division, thus feeding the cycle.)

Shared values unite. Differences divide. Those shared values can bridge gaps created by the wildest of differences when they are founded upon absolute truth.

PLUGGING MYSELF, YEAH, LET’S GO

Want to read more of my writing? Inner Demon, a fantasy story about identity and found family, is available nearby everywhere in ebook, and it’s also in print and, more recently, audiobook. Check it out! Or if dark science fiction is more your taste, go check out The Failed Technomancer.

- Which I recommend checking out, by the way. Tanner is much more philosophically focused than I tend to be, and his target audience is primarily writers, but I say that just to make sure you check out his space with the right expectations—anyone can learn something interesting from his thoughts. ↩︎

- If I’m not being clear here, stating that human beings are meat computers is a literal observation if what is meant is that our brains store and access data, have electrical impulses, powerful unconscious routines, and other traits that make us comparable to computers; such things appear to be indisputable parts of our nature. But stating that human beings are meat computers is a philosophical observation if that is claimed to be the sum totality of human existence; you are positing a claim about human nature, and objective reality—which I think is utterly false. The existence of unconscious subroutines and conscious thought that sometimes can be proven to come after a subconscious routine does nothing to prove that only chemicals are at the wheel, and poorly explain human ability to self-reflect and choose to change (or otherwise rise about environment). ↩︎

- I must note that I haven’t done any research to back up Mr. Rogers’ claim about the discovery of quantum mechanics. My point in this instance is not to weigh the accuracy of his data, but to point out a massive hole in his logic—if he genuinely believes that what he said is true, he came to the exact opposite conclusion of what the evidence actually points to. ↩︎

- Why… Why do the dumbest, worst takes almost always feel the need to include Hitler and/or Nazism at some point? The lack of creativity… and the total ignorance of other perfectly legitimate genocidal regimes who espoused the most evil and disgusting of ideologies! ↩︎

- You’ll notice that, as such, I generally use “absolute reality” and “absolute truth” interchangeably going forward—and conjugate verbs as if referring to something singular, despite sometimes saying both. That’s because they are essentially the same thing. ↩︎

- I prefer my elephants cooked medium-rare, and I prefer steak over ground meat. ↩︎

- I will note that no one has disproven that gravity is caused by spirits, although if so then these spirits are extremely consistent about pulling objects with less mass toward objects with greater mass (and ignoring pleas or bribes to act to the contrary—in other words, they act exactly like natural laws).

I’m not saying I believe this explanation on any level, but I am defending our ancestors and historical cultures a little bit. They didn’t possess the foundation of knowledge we have now and their conclusions that seem utterly insane today were often quite reasonable based on what they knew—or thought they knew. What they incorrectly thought was absolute truth.

On the other hand, I’m quite confident that they possessed shades of absolute truth that we no longer have today, making it quite foolish to write off learning about them entirely. And, no, I’m not referring to their scientific learning, generally speaking ↩︎ - In my mind, “good” can be defined as “seeking after and living according to absolute truth”; evil is the absence of good. ↩︎

- I must note that this is an extremely stunted analysis of Christianity—the God of Israel’s Will is to produce a people who are obedient by choice, to produce people who are good because they want to be good for its own sake, not because they are forced to. (And then there’s Jesus Christ making this all possible through His atonement and taking the sins of mankind upon Himself.) The fact that God is capable of forcing them to obey His will and chooses not to is a very significant part of Christian theology. Most gods that I’m aware of would force all into worship and obedience if that were an option.

In addition, I don’t think Christianity would work if God weren’t all-powerful, and therefore the ultimate force capable of violence. Souls who don’t follow His commandments won’t be able to resist or avoid their ultimate punishments; if they try, they will be forced that direction. If this weren’t the case, the inhabitants of Hell could rise up and move into Heaven, making statements about reparations, privilege, crime being caused by economic or social status, and the like while performing mass stabbings.

Taking this to the extreme, if the Devil were equal in power to God, and therefore theoretically able to overthrow Him if given an upper hand—well, that version of Christian theology would be utterly alien to the theology that actually exists.

I must also state the hopefully obvious truth that might does not make right—power can be wielded by the good in defense of what’s true or the evil to further what’s wicked, making power no better or worse than its possessor. In this life. It is my opinion that righteousness and power are inextricably linked in the worlds beyond, but for whatever reason they have been decoupled in this world. ↩︎ - Note that standard of living does not solely point to accumulation of wealth—while it is true that those who create strong families typically are better off than those who don’t, they also aren’t, to my knowledge, unusually likely to be exponentially wealthy either. They appear to have a higher predilection toward minimum necessary degrees of security, which, by definition, is all anyone really needs. They are more likely to be higher in other sources of happiness, even before the point where wealth has been accumulated to the level where it ceases to be linked to happiness. ↩︎

- I also want to note that these principles can be applied at broader scales—as an example, some human cultures contain greater or lesser portions of absolute truth, but none of them contain all of it. All have cultural psychoses that sometimes are amusing to outsiders, sometimes are harmful. (And some cultures are nothing but psychosis… Yes, some cultures are objectively worse than others. Just look at their end results.) ↩︎

- And listen—not everyone who reads this believes in God. Whether or not you believe that there exists an entity that personifies absolute truth, all these principles still stand, still function, and are still applicable in the real world, because absolute truth still is. ↩︎

- Good golly, anyone who doesn’t understand some of these lines to be sarcasm is going to be so incredibly confused by these tonal shifts. ↩︎

- And in this way I continue to grin and giggle as I bring up examples and references that I know shouldn’t be inflammatory but absolutely will be to specific crowds, particularly those who think of themselves as the being most tolerant. ↩︎

Leave a comment