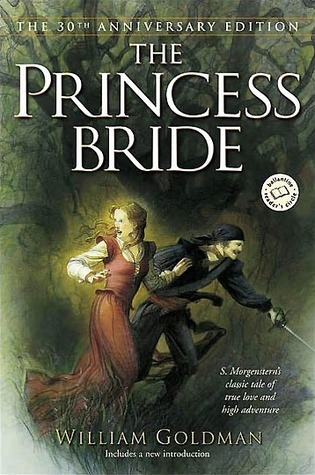

The Princess Bride is legendary. Infinitely quotable, a cult classic of its time, a moderate box office success with a long, long tail of movie purchases and rentals, I don’t think I’m being in any way controversial when I say that The Princess Bride will endure the test of time as long as visual media exists.

And, let’s be honest, “Inconceivable!” and “As you wish,” among other lines, might just survive an apocalyptic event that returns mankind to the stone age.

But here’s something a surprising number of people don’t know: The Princess Bride was a book before it was a movie. In fact, the book predates the movie by over a decade.

It’s a real shame, because The Princess Bride is one of the few instances where the book and the movie are equally excellent, despite the many meaningful changes that occurred during adaptation. So, in this blog post, I want to discuss both.

For the sake of clarity and brevity, rather than always differentiating the two versions of The Princess Bride by adding “book” or “movie,” or a year, after the title, I’ll generally refer to the original book as “the book” or as “The Princess Book” (TPB for short) and the movie adaptation as “the movie” or “The Princess Movie” (TPM).

The Princess Brides (An Overview)

The Princess Bride was written by William Goldman and published in 1973. The book has the fictional framework of being a narrative history of sorts originally written by a man named S Morgenstern—”[A] Classic Tale of True Love and High Adventure”—which Goldman’s father read to him when he was a boy. Within this framing device, Goldman later, as an adult (and, notably as a heightened version of his real self), tracked down a copy of the book and discovered that it was hideously long, meandery, and preachy,1 really only masquerading as a story, which his father only made interesting by skipping to the good stuff. Goldman then “abridged” this tome to match his father’s handling of it, turning it into the pseudo–fairy tale that we enjoy today.

Speaking of the movie—The Princess Bride film adaptation was released in 1987 and, like the book, the script was written by William Goldman.2 Goldman was also deeply involved with the film’s production, though he wasn’t the director—Rob Reiner filled that role. The movie also makes use of a framing device, this time of a young boy who is stuck at home, sick in bed. Looking to help him out, the boy’s grandfather stops by and offers to read him a novel called The Princess Bride. Throughout the movie the camera swaps between this framing device and the events within the novel.

Different in Spirit, Equal in Execution

As far as I’m concerned, William Goldman is the boy in the movie’s framing device. Yes, there are some inconsistencies of details: in the book, the boy’s father reads The Princess Bride to him, while the movie gives the role of reader to the boy’s grandfather; there’s also the fact that the book as it exists in the movie appears to be an actual story that doesn’t need significant abridgment to be made palatable, unlike The Princess Bride‘s unabridged version as written by S Morgenstern in the book’s framing device. But Goldman’s insertions into his “abridgment” include moments where he relates memories of his dad reading to him while he’s sick in bed, and during a scene where Buttercup is nearly eaten by sharks his father comforts his son and let him know that Buttercup lives—asides and inserts like this one in the book surely directly inspired the movie’s framing device.

I suppose the grandfather in the movie could, alternatively, be interpreted as Goldman himself, wielding his abridgment of his favorite childhood story and coming to rescue his sick grandson from boredom and Nintendo… The bigger point here is that the movie’s framing device is a natural and respectful extension of the book’s framing device, translated in such a way as to better fit the unique strengths of film.

That spirit of natural and respectful adaptation is present in every change between the two stories, and is a major part of what makes them unusual equivalents (and complements) to each other in a way that isn’t often felt in book-to-film translation.

To begin with broad differences between the two, there are a handful; the difference in framing device is one. There’s also a large difference in tone.

The first morning after Westley’s departure, Buttercup thought she was entitled to do nothing more than sit around moping and feeling sorry for herself. After all, the love of her life had fled, life had no meaning, how could you face the future, et cetera, et cetera.

The Princess Bride (30th Anniversary Edition), page 56

I didn’t alter that quote at all, it is word for word. The book can be very droll, and I’d even go so far as to say sarcastic at times in its parody. Buttcerup’s blatant airheadedness, as well as Westley’s seeming inability to (early on) say anything without adding the detail that he loves Buttercup, and other things all poke fun at a lot of damsel-in-distress fairy tales. Westley suddenly, and unexpectedly, “dying” twice—first to the Dread Pirate Roberts, and later to the Machine—are also subversions of what might be expected from this type of story. Yet I think this tone would have sucked the energy out of the movie adaptation, which may be why the movie went tried to be much more sincere (while still retaining self-awareness and levels of parody). Whatever the reason for the differences, what each does differently works within its own context.

This difference in tone is probably what drives most of the changes between the two stories, and I bet is directly responsible for the massive difference between their endings—which also happens to be the best example of what I’m trying to share. The movie ends with Westley, Buttercup, Inigo, and Fezzik escaping from Prince Humperdinck, and with Westley and Buttercup sharing a kiss described as surpassing all other kisses in human history,3 and with the grandfather finishing reading to his grandson and the grandson asking for him to come back and read it again. This is all very fitting with the book’s much more sincere, sometimes fantastical, and generally more optimistic tone, and leaves the audience with a pleasant feeling for some time afterward.

But the book… Well, the book continues right past where the movie leaves off our named heroes. It doesn’t take long for Humperdinck to free himself from his restraints and he immediately gives chase; Westley and the others may be on the fastest horses in Florin, but even the fastest horses don’t do you much good when Fezzik gets lost, Inigo’s wound reopens, Westley’s “condition” (of having been dead) begins relapsing, and Buttercup’s horse throws a shoe…

Much, much grimmer of an ending than the movie.

To be fair, one of the elements of the book’s framing is that Goldman makes his own insertions into the abridgment, often to make up for “cut” text, but he uses these insertions to add his own thoughts and interpretations here and there. He does explicitly state that “they got away,” and that “[they] got their strength back and had lots of adventures…” but he refuses to tell you how. And… well, here are the book’s two last paragraphs.

But that doesn’t mean I think they had a happy ending either. Because, in my opinion anyway, they squabbled a lot, and Buttercup lost her looks eventually, and one day Fezzik lost a fight and some hotshot kid whipped Inigo with a sword and Westley was never able to really sleep sound because of Humperdinck maybe being on the trail.

I’m not trying to make this a downer, understand. I mean, I really do think that love is the best thing in the world, except for cough drops. But I also have to say, for the umpty-umpth time, that life isn’t fair. It’s just fairer than death, that’s all.

If that doesn’t put a wry smile on your face, you might not appreciate the book’s sense of humor.

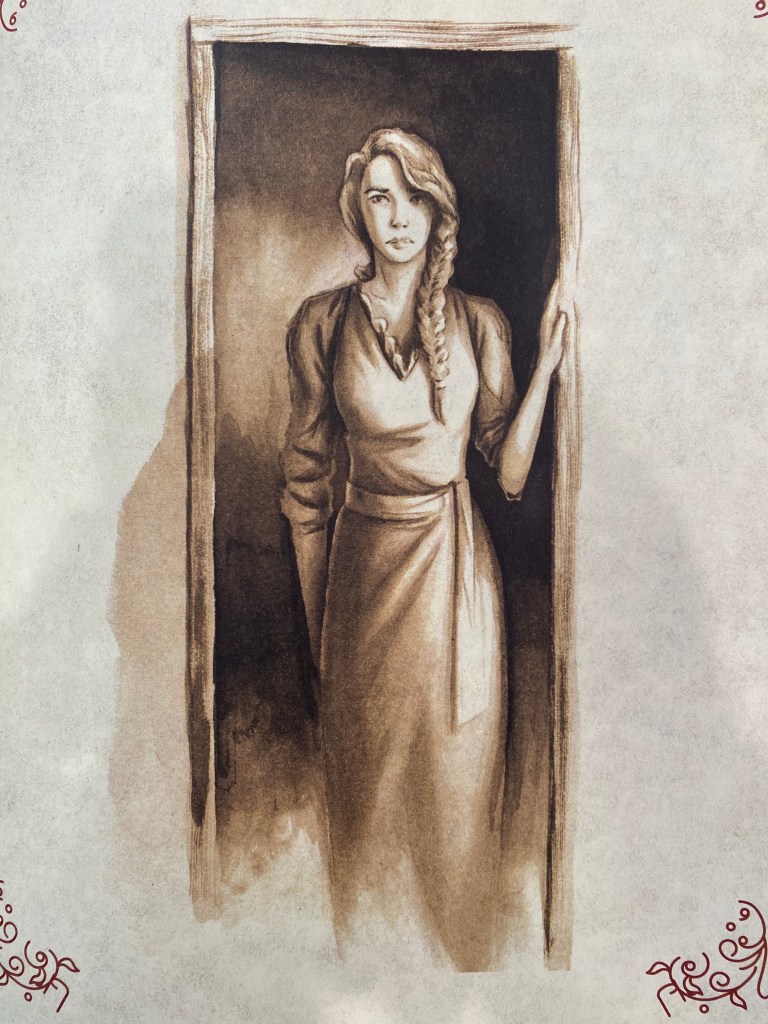

Changes in Content and Substance

The Princess Book, probably predictably, also has a lot more story to it than The Princess Movie. For example, the opening scene with Buttercup and Westley lasts perhaps five minutes in the movie; it’s over thirty pages in the book, includes additional characters (Buttercup’s parents, the Countess), discusses the most beautiful women in the world (and Buttercup’s unintentional rise to overtake every last one of them), and gives a much more thorough view into Buttercup’s growth from a girl into a woman—and her process of falling in love with Westley most unwillingly. (Unwillingly against herself, that is—no one forces her to love.)

Fezzik and Inigo both get entire chapters dedicated to their backstory; Prince Humperdinck as well. Details in these chapters are only hinted at or alluded to in the movie, or dropped entirely. The “courtship,” such as it is, between Buttercup and Humperdinck gets a (short) chapter in the book, but it’s essentially hand-waved in the movie.

There’s a good reason for all of this abbreviation, and it happens in nearly every book-to-movie adaptation: movies are not capable of including everything that a book is capable of, nor should they try. Attempting to do so would result in a bloated film that would likely be better off as a television series instead, if such an effort must be attempted4; in fact, if The Princess Bride were adapted to film with the intent of including every detail possible, I think it would be a very long miniseries of television (with many episodes that exist primarily or solely for exposition), but probably better off structured as two or three seasons of television—maybe more, given modern episode counts.

I don’t think any of these cuts and abbreviations exist solely because of media translation, however. Or, better said, what was chosen to be cut and abbreviated was done so expertly; they were effectively used as tools to accomplish the movie’s vision, which, among other things, includes being a bit more optimistic and a lot more sincere than the book—while still remaining a parody of fairy tales, of course.

There are other changes that I might suspect were made first for budgetary reasons rather than reasons of concision, but still were effectively made to serve the above-mentioned tonal shift well; Prince Humperdinck’s Zoo of Death comes to mind.

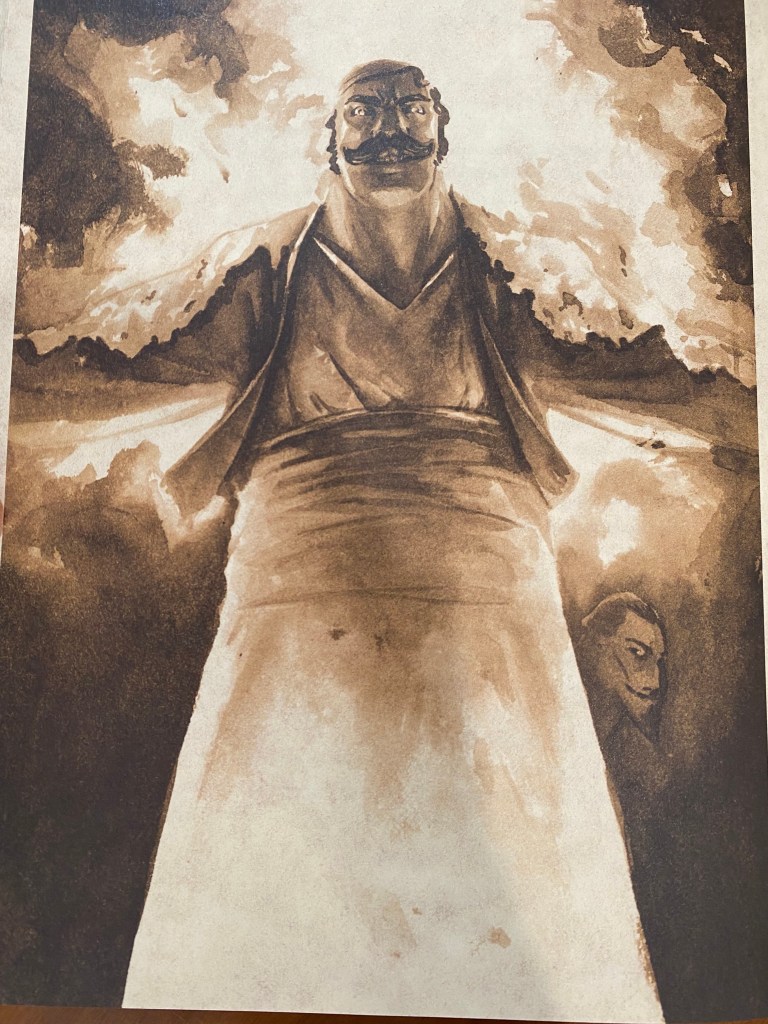

In the book, Prince Humperdinck is an even more villainous figure. His introductory chapter begins with a description of his hunting habits and his deep love of killing things—well, let me allow Goldman to do the talking.

[Humperdinck] made it a practice never to let a day go by without killing something. It didn’t much matter what. When he first grew dedicated, he killed only big things: elephants or pythons. But then, as his skills increased, he began to enjoy the suffering of little beasts too.

This is followed by Humperdinck wrestling an orangutan into exhaustion and then killing it by crushing its spine—with his bare arms, notably. Perhaps it’s for obvious reasons that such content, while amusingly delivered in the book, would hit very differently if delivered visually.

Of course, we also end up losing amusing interactions like the following quote, a part of the above scene, so the movie wins some points for keeping things PG while losing other points for missing out on feathering its hat with more quotable moments:

“Your father has had his annual physical,” the Count [Rugen] said. “I have the report.”

“And?”

“Your father is dying.”

“Drat!” said the Prince. “That means I shall have to get married.”

Oh, the horror!

And finally, while this is by no means a complete or completely detailed list of all the differences between The Princess Book and The Princess Movie (else I would need to summarize the long and detailed Fezzik and Inigo backstories, among other things), I want to bring up one more class of change that… just exists? You’ll understand what I mean in a moment, but there are some changes that appear to solely exist just because, or maybe to make the movie slightly more fantastical.

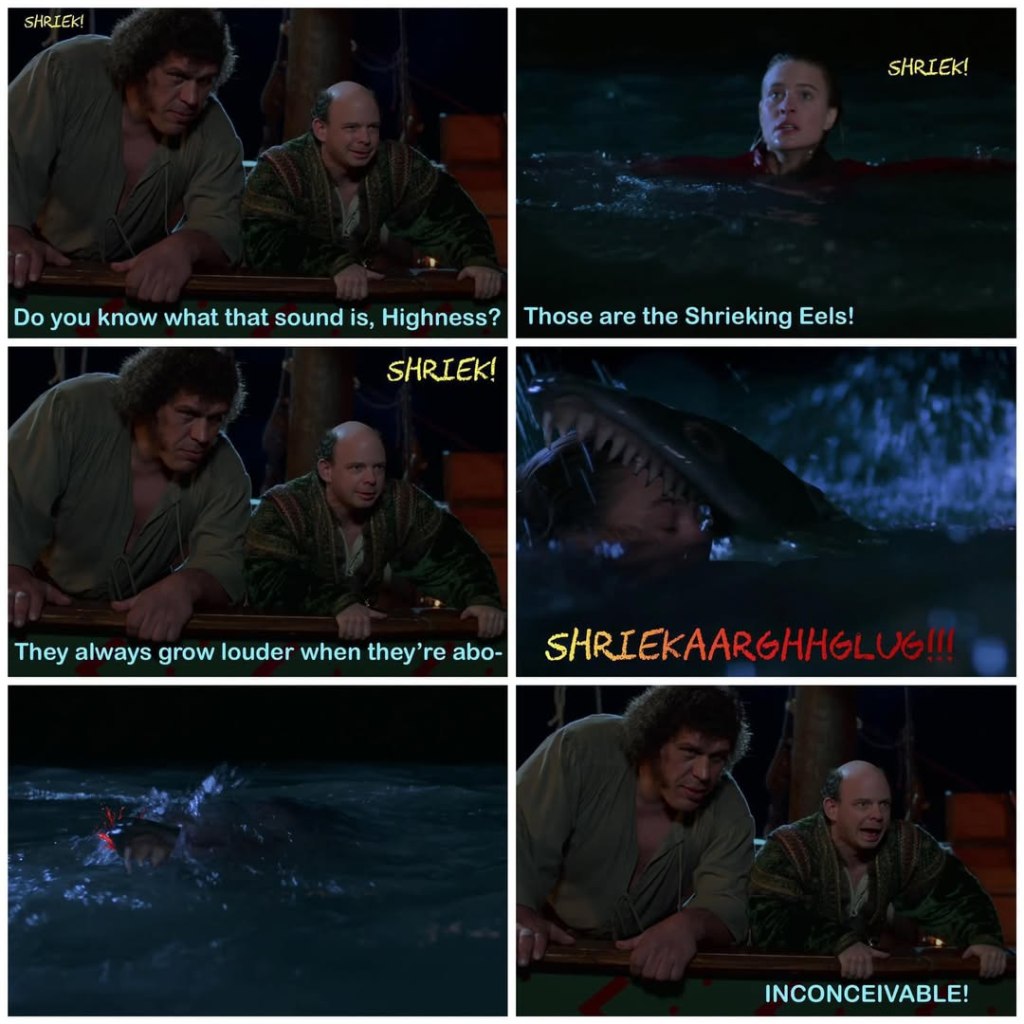

Like the screeching eels.

In the book, Buttercup isn’t in danger of screeching eels—she’s in danger of regular sharks. And Vizzini (only referred to as the Sicilian thus far) gets the sharks into a blood frenzy by cutting his arms and legs and tossing his blood into the water. This is one of the few instances where I think the movie is objectively better, rather than equal but different.

The Same, But Different

The differences in tone and content aren’t the end of what makes the two The Princess Brides distinctly different. Even shared moments just come across better in one format.

Again, this isn’t a comprehensive list, but just two examples, one favoring for each.

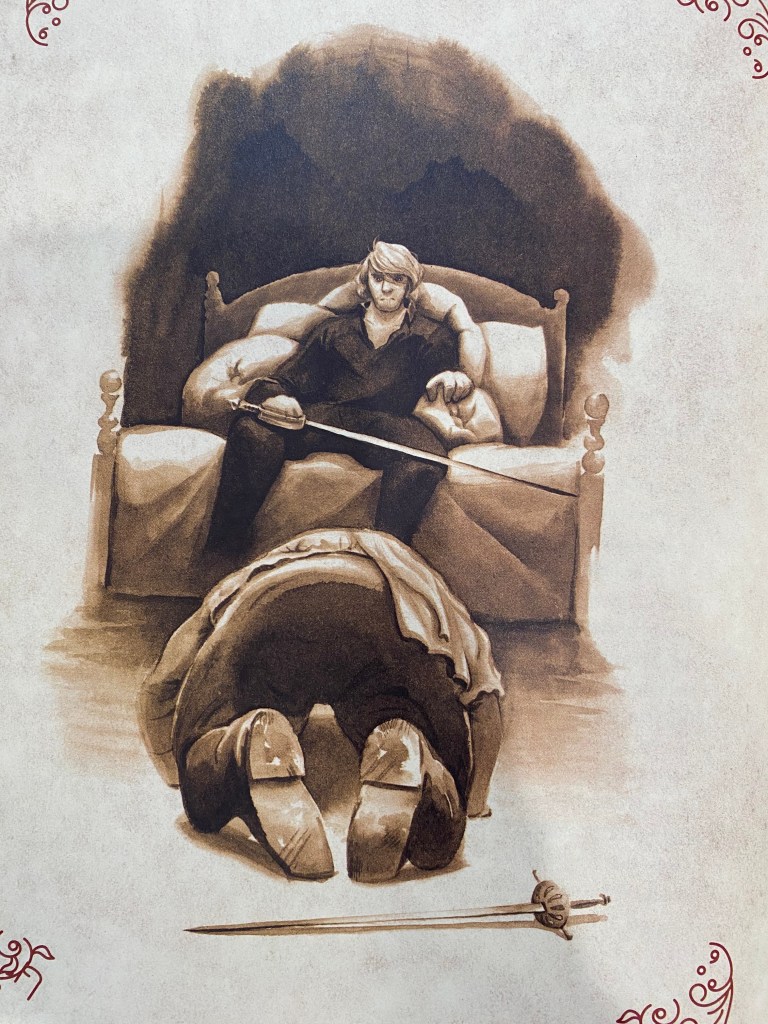

Now, let me make something clear: Inigo Montoya finally avenging his father and slaying Count Rugen is beautiful no matter how you experience it. It’s the culmination of Inigo’s arc, it’s the death of a vile villain, and it is resolved through an intense, powerful struggle, a true battle of good versus evil—and it truly is, in the sense that Inigo flawed-but-good and is slaying a wicked man, thus preventing Rugen from ever causing harm again.

But, at the same time, it isn’t, and I’m more impressed with how the movie accomplishes that subtlety.

Now let me back up a bit. True to form, The Princess Book has a lot more than The Princess Movie. There’s much more switching of perspectives, and specifically I mean most of Inigo’s chase of Rugen is broken up into very small pieces (so we can keep up with the actions of the other characters at the same time); we even cut away the moment Rugen buries a dagger in Inigo’s gut, leaving us despairing for Inigo’s fate.

For about a page, anyway. Yeah, that’s it. Just a page.

This scene also has way more going on in the book than in the movie. In the book, we get a detailed description of the unique type of dagger that Rugen uses to “rearranged [Inigo’s] insides.” We also are inside Inigo’s head and see both his father, Domingo Montoya, and his old swordmaster, MacPherson, sort of encouraging Inigo on, but mostly berating him for his failures.

And then at the end of the scene, Inigo doesn’t actually kill Rugen. Inigo stabs the Count to the left of his heart, explains that he’s cutting out Rugen’s heart the same way Inigo’s heart was cut out when he was a boy and he watched Count Rugen kill his father in cold blood, then stabs again—

Then Count Rugen drops dead from terror.

“Inigo looked down at him. The Count’s frozen face was petrified and ashen and the blood still poured down the parallel cuts. His eyes bulged wide, full of horror and pain. It was glorious. If you like that kind of thing.

Inigo loved it.

There’s good reasons why the book handled this scene this way. For one, it’s still powerful, and it’s still satisfying. After all, in the book the reader spends much, much more time with Count Rugen and his studies into torture and fear, and there is a sort of catharsis, a beautiful irony, to have Rugen’s ultimate obsession, fear, be what really kills him in the end. So I’m not saying the book is bad by any means, and I’m certain there are those who vastly prefer the book’s interpretation.

All that said, I like the movie’s better. It’s simple. It’s straightforward. I think the lack of extraneous, potentially distracting detail makes it more powerful. Inigo arrives. The dagger hits him, and you feel it. Mandy Patinkin sells every moment in this scene, you see it in his eyes. Then he finds his strength, he stands, he faces down his demon of so many years, and he slays him.

Even Inigo’s killing quote is slimmed down just slightly in the movie and, in my mind, improved: I want my father, you son of a bitch hits me just a little harder than I want Domingo Montoya, you son of a bitch.5

But both scenes absolutely nail what I was alluding to earlier: Inigo Montoya is not a true hero in this moment. In the fairy tale sense. In the movie, rather than being met with triumph and ecstasy and all sorts of other heroic narrative rewards for overcoming his demon, Inigo is left alone with a corpse, in a quiet room, with one hand holding together his insides and staving off the results of a potentially fatal “organ rearrangement” via Florinese dagger. Nothing in the larger narrative is resolved, just Inigo’s personal narrative, and even then the moments immediately following Rugen’s death are poignantly quiet and flat. Inigo stares at Rugen and, rather than celebrating, stumbles off after just a moment.

In the book, Inigo briefly revels in Rugen’s fear, agony, and death, and then sets off, still experiencing just as much total lack of glory or narrative reward for heroism. His life’s mission is fulfilled and now he has nothing.

What The Princess Bride, both versions, intrinsically understands is that Inigo Montoya did not do wrong in avenging his father and slaying an evil man, but it also does not justify his methods in doing so. By dedicating his entire life to killing the six-fingered man, Inigo was left with no wife, no children, no home, nothing that he had any investment in or long-term, meaningful positive effect on. His entire life was geared toward a literally negative end-result, of removing something, and even though what he did was an objectively good thing, he completely failed to live along the way.

Inigo was a ghost in his own life. If Westley hadn’t offered him purpose near the story’s end, he likely would have died—in spirit if not in body—shortly after Rugen’s death.

Inigo rebuilding his life, finding purpose, and creating a family after his father’s death, and then never encountering the six-fingered man again—well, it wouldn’t have made for as good of a story. It wouldn’t have been a strong creative choice for this story, anyway. It would have been objectively better for Inigo as a person—but Inigo is a character. As well, since evil must be destroyed, there still would have been a sense of something lacking.

No, the theoretical best of all worlds would have been for Inigo to have more to fight for than just his dead father, but to still kill Rugen in the end.

But, again, don’t get me wrong—Goldman did incredible work with both versions of his story. I am not advocating that the story itself should be any different. Part of what makes both hit so powerfully is explicitly the fact that Inigo got exactly what he wanted, it left him with nothing, and that was portrayed effectively. The Princess Bride would have been a weaker story had Inigo been a better person and lived a better life. It’s good to portray flawed characters and the natural results of those characters’ flaws.6

But it’s also impressive how the movie is able to convey all of that same deep meaning without needing nearly as much extra information conveyed through extra scenes and asides.

As for something I think comes across better in the book, I’m going to choose Westley’s condition (of being/having been dead). In the book, it’s clearer that the miracle Westley is made to consume isn’t at full efficacy. The book also is better able to track exactly how much time has passed by telling the reader the exact times various events happen—a much greater feeling of urgency and tension is built as the book hurtles toward its dramatic conclusion, toward a confrontation between Westley and Humperdinck, but you as the reader the entire time feel every grain of sand dropping through the hour glass as you learn by the minute how much longer Miracle Max’s miracle is going to work.

And then see the clock run out.

I think this makes Westley’s bluff of Prince Humperdinck, and his To the pain! speech, that much more satisfying. I both know that Westley ran out of time for certain, but also that he managed to make things work, miraculously, anyway.

To One, But Not the Other

One inevitable result of The Princess Book and The Princess Movie containing scenes that don’t exist in the other—combined with the overall high quality of the two—is that, inevitably, one is going to have an iconic moment that the other entirely lacks. I opened up this blog post with a picture of one. At the end of the movie, after all has been said and done and Westley and Buttercup are reunited in romantic love, the sick boy asks his grandfather if he can come back tomorrow and read the book again.

And the grandfather tips his hat and says, “As you wish,” a deeply moving display of familial love made all the more impactful by everything that had come just before.

Returning to the book—the Zoo of Death does not exist at all in the movie, so every moment of Fezzik and Inigo working together to infiltrate that place and to rescue Westley, their unique strengths and weaknesses complementing each other so perfectly to overcome Prince Humperdinck’s death traps, it all can can only be experienced in the written word.

Other Uniquely Movie Elements

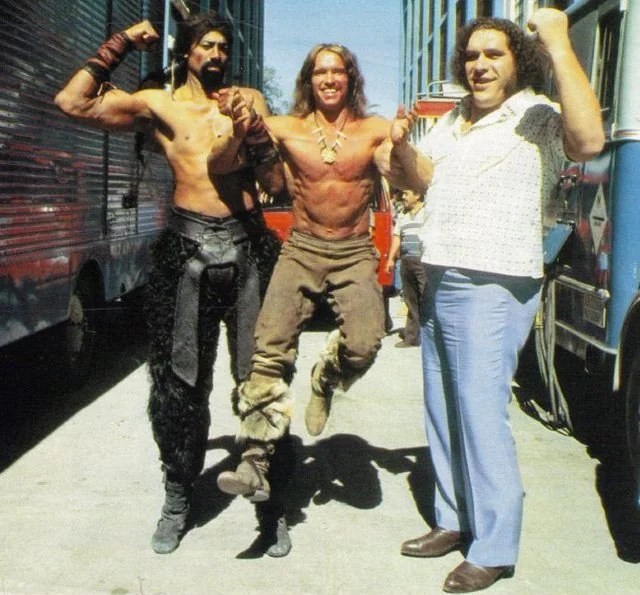

After all of this, there are two things I want to briefly mention that are unique to the movie experience, but which I don’t want to directly compare to the book, as I don’t think it would be fair. Those things are two actors in particular: Andre the Giant and Billy Crystal.

(As a quick aside: Every actor did his or her job and did it well in The Princess Movie. A book is, generally, the pure creation of one individual—or one central individual—but movies cannot come together without a multitude of artists coming together in a shared vision. Not bringing up other actors is not a knock on any of them. I just have more to say about Andre and Billy.)

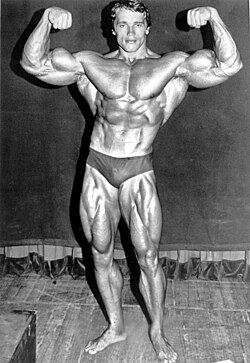

Interestingly enough, at one point the role of Fezzik was considered for a different man famous for his physique, who was not born in the United States, and who also had a very distinct and famous accent. That man was Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Yes, THAT Schwarzenegger. The one who would be back—for a different franchise.

Since Schwarzenegger was not the final choice for Andre the Giant, we can only speculate how different The Princess Movie would have been. I have a hard time imagining Schwarzenegger being a good Fezzik, or at least better than Andre the Giant ended up being, but maybe he could have been equally good.

Very good… and utterly different. the ripple effect would have been felt through the entire movie. Just look at the literal, real-world size difference between the two:

Yeah. That’s Andre the Giant, to quote Bluey, for real life. No camera tricks were necessary to make him the imposing figure he was in the movie. Due to giantism, Andre the Giant was literally that big. And I don’t think any normal-sized man, even one as muscular as Schwarzenegger, could have hoped to have had the same imposing presence as a literal giant.

I’m curious why Andre the Giant wasn’t equipped with a mustache for the movie, unlike the emphatically Turkish Fezzik of the book, but Fezzik’s movie sideburns are a different sort of iconic.

As for Billy Crystal, no one on this planet, now or then, could have made Miracle Max as iconic. No one. According to commentary in the anniversary edition of the book, the director had to be removed from set while recording Billy’s scenes because he kept laughing too hard; many scenes were reshot because Mandy, Andre, and Cary (Inigo, Fezzik, and Westley) couldn’t stop laughing; and supposedly Billy improvised so much material that they could have added another hour to the movie of just Miracle Max standup comedy.7

The Miracle Max scenes in the book are still funny and memorable, but Billy Crystal apparently was just the right guy, so perfect for this role that it will forever belong to him. Even when reading the book, I feel like I’m missing something when I read Miracle Max say that true love is the best thing in the world except for cough drops, rather than except for an MLT, specifically where the mutton is nice and lean, and the tomato is ripe… They’re so perky! I love that.

Other Uniquely Book Elements

And as a final random note, did you know that William Goldman put some effort into a sequel for The Princess Bride called Buttercup’s Baby?

Boy howdy am I glad that never fully realized.

The Princess Bride is a perfect story as-is. It both didn’t need a sequel and a sequel have gone entirely against the book’s closing lines about you imagining the details of what happened to Westley and Buttercup after The End. The Princess Bride is strongest as a single book (and movie).

That said, apparently William Goldman was pestered by fans for years about a potential sequel. I have to wonder if this pressure is what resulted in the single published chapter on the could-have-been book.

The name of that chapter: Fezzik Dies. It sort of continues right where The Princess Bride left off, once again as an abridgment of a fictional story with many asides.

If you’re interested, you can read the chapter in any anniversary edition of The Princess Bride—I’m unaware if the chapter has become a standard addition to traditional copies of the book. In either case, judge for yourself if the world was saved by this sequel never being finished, or if we should mourn for missed majesty.

Wrapping it Up

If at any point in this post I suggested that the book or the movie is wholly superior to the other, let me correct the record no: No! No, no, absolutely not. Read The Princess Bride; watch The Princess Bride. You will get complementary experiences with strengths in one area and weaknesses in others. You will get a more whole experience by taking in everything one has that the other doesn’t. You’ll still get a good variety of experience, and contrasting the book’s droll tone with the book’s more sincere tone might lead you to some interesting insights.

Which leads everything to make me want to ask… Why do they both work?

I don’t know. That’s the anticlimax.

I don’t believe it was because both were written by the same author. To my knowledge, book authors have a poor record of adapting their own work to film, although William Goldman is unique in that regard by being a very talented and experienced author and scriptwriter. And I can’t say it’s because the movie stays totally true to the book because there are substantial differences between the two, risky differences that could have been infuriating or come across as disrespectful to the original book.

Perhaps the answer simply is that adapting art between media is, in and of itself, an art. Figuring out what to keep, what to leave, and what to change, may have some objectively right or wrong answers, but it will also have many, many subjective answers. Figuring out how to take what works uniquely well in one format, but not another, and then translating those required elements is very tricky. In short, maybe Goldman is the unique answer, since he performed that translation.

I love The Princess Bride, both versions. I wanted to talk about them, and I wanted to recommend the book to the many people who have seen the movie and didn’t even know a book existed. I hope you enjoyed this exploration of the two.

Enjoy this? Please consider subscribing! I post new blog posts most weeks. Most of my posts are reviews, but I also share a lot of updates on my own books.

If you’re interested in trying out one of my books, The Failed Technomancer and Inner Demon are both available to be read on my website (in whole for the former, in part for the latter), or you can buy them here and here, respectively.

- Amusingly enough, another part of the story’s framework is that S Morgenstern was an absolute master of storytelling, so his bafflingly terrible creative decisions for this book have no good explanation. ↩︎

- The purpose of this post isn’t to discuss Goldman’s body of works, but I want to state somewhere that this man has many other well-regarded pieces of art to his name. As far as film concerned, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid is one; All the President’s Men another. The Princess Bride is among his best-known novels, but his other best-known is a thriller titled Marathon Man. ↩︎

- Amusingly enough, this exact moment—of Westley and Buttercup sharing that perfect, passionate kiss—happens at the beginning of the book. ↩︎

- And it’s debatable whether or not even that is a good idea. *nervously glances at HBO’s upcoming Harry Potter reboot* ↩︎

- As a side note—while I tolerate swearing, I’m not generally a fan of it, yet I’ll die on the hill that any softer language in this quote undercuts the power and ferocity of the moment, as well as Inigo’s pain and his own imperfection. ↩︎

- As a side note, I think this is also a key part of what makes The Princess Bride an anti-fairy tale, and a good one. Heroes don’t need to be perfect in fairy tales, of course, but they are traditionally idealized—meanwhile, in this story, Inigo is driven solely by non-heroic vengeance that destroys his life. Westley is no better, being a pirate that we have every reason to believe has spent years murdering and robbing, who also can be cruel to Buttercup, most notably when he first rescues her and as part of his “To the pain!” speech. (This really only comes through in the movie in the scene where Westley, among other things, says “For where I come from, there are penalties when a woman lies” and threatens to strike Buttercup. Some interpret this as Westley messing with Buttercup; I’m not convinced there isn’t at least a kernel of real behavior in there.) ↩︎

- I’m rather disappointed that didn’t end up in a special anniversary edition of the DVD, so far as I’m aware. ↩︎

Leave a comment